In the corporate lexicon of the 21st century, few compliments are as double-edged as being called a "rockstar" or a "wizard." These terms imply a capacity for labour that transcends the normal, suggesting that the worker possesses a limitless reserve of energy, capable of conjuring results out of thin air. Aminder Dhaliwal’s graphic novel, A Witch’s Guide to Burning, instead reveals how in a patriarchal society, this demand for magic is not a metaphor for excellence but a death sentence. By reimagining the exhaustion of the modern worker through the fantastical lens of witchcraft, Dhaliwal offers a searing critique of a system that fuels its growth by incinerating its most valuable resources. This is why her work is aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of Decent Work And Economic Growth and Gender Equality.

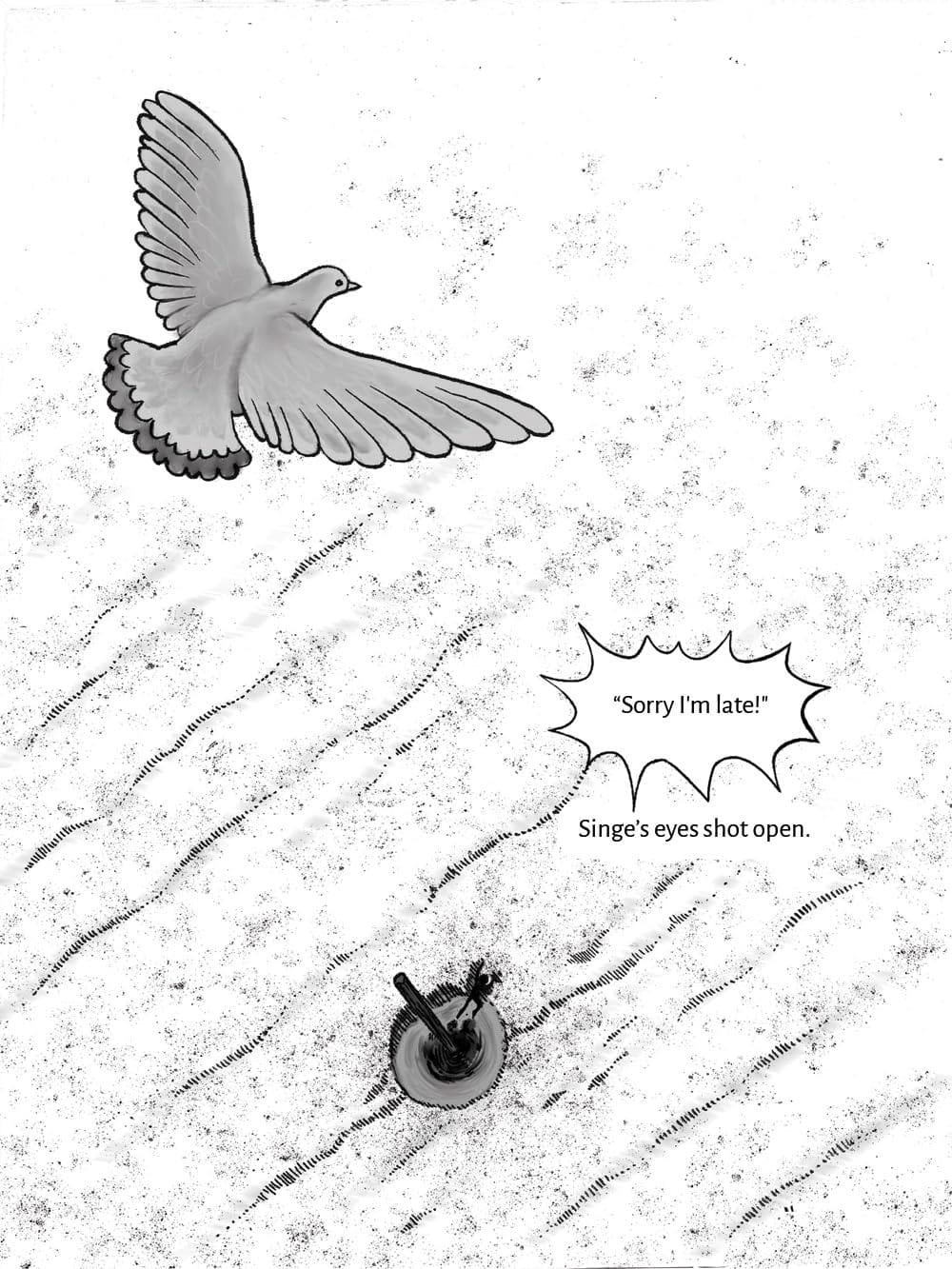

The story introduces us to Singe, a young witch living in the fictional Chamomile Valley. In this world, witches are not hunted for their heresy; they are employed for their utility. They serve their communities, ensuring the crops grow and the economy thrives. However, this social contract comes with a brutal clause: if a witch’s magic begins to fade—often the inevitable result of overexertion—she is deemed "useless." The community then performs a "cleansing," a euphemism for burning the witch at the stake to make room for a fresher, more productive replacement. Singe, having been drained by the relentless demands of her village, finds herself tied to the pyre. She survives only because a sudden rainstorm extinguishes the flames, leaving her alive but stripped of her memories and her magic.

Through Singe’s harrowing journey, Dhaliwal creates a powerful allegory, with the act of “burning her at the stake" performing a visceral representation of occupational burnout—a phenomenon the World Health Organization now recognizes as an occupational hazard resulting from chronic workplace stress. In Dhaliwal’s Chamomile Valley, as in our own "hustle culture," the worker is commodified to the point of disposability. The economic growth of the town is prioritized absolutely over the health of the human capital that sustains it. When Singe can no longer produce "magic" (read: surplus labour, overtime, emotional management), she is discarded. This narrative arc challenges the sustainable development ethos, asking a critical question: can an economy truly be healthy if it requires the ritual sacrifice of its workers’ well-being? The allegory deepens when viewed through the lens of gender equality. It is no coincidence that the "burnt-out" workers in Dhaliwal’s world are witches—figures historically assigned to women. The expectation for women to perform "magic" in both the workplace and the domestic sphere is a pervasive social pressure. Women are often expected to make difficult tasks look effortless, to manage complex emotional landscapes without complaint, and to be perpetually useful to others. Dhaliwal connects the historical persecution of witches—often independent women who threatened the social order—to the contemporary exploitation of female labor.

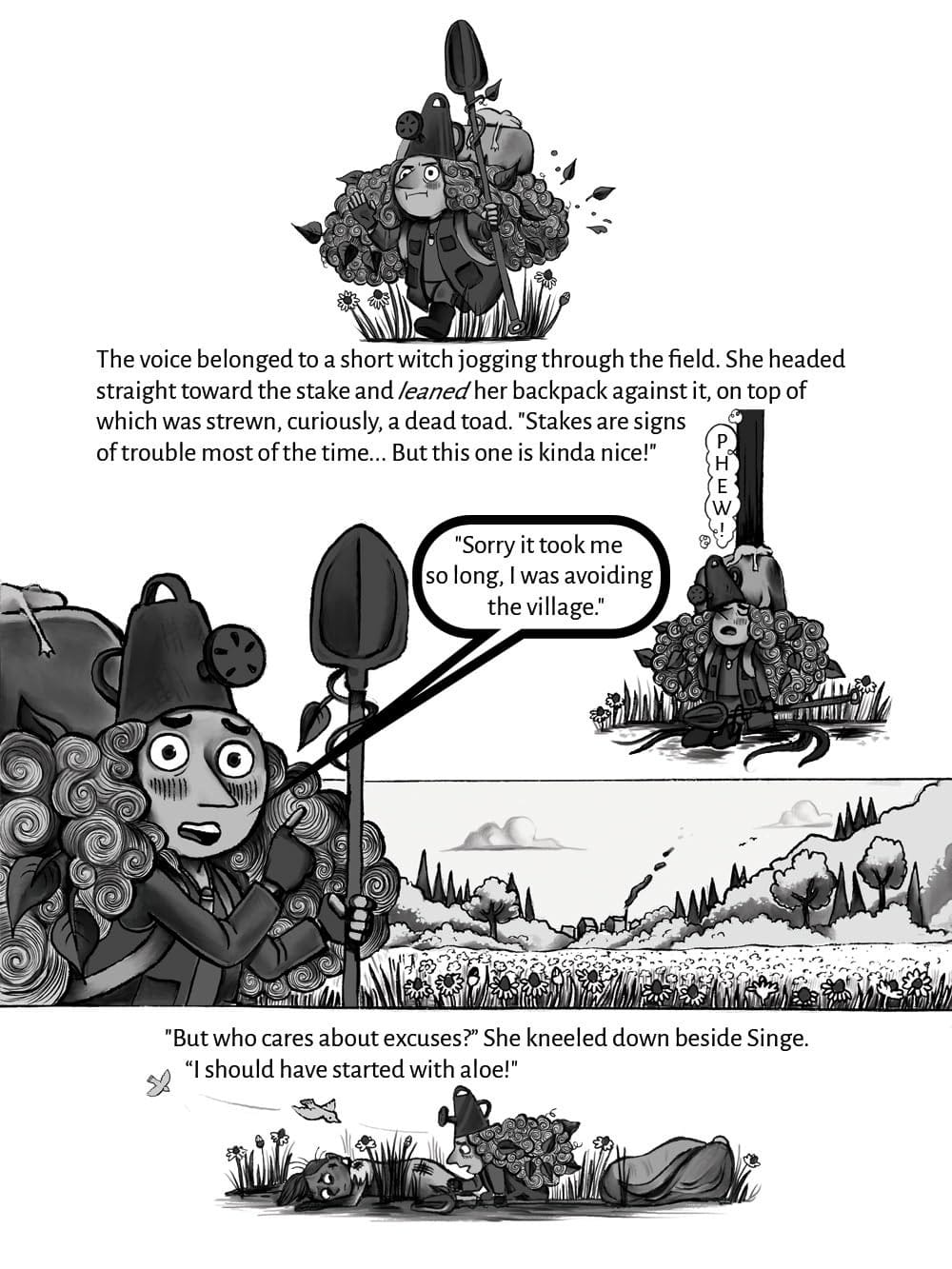

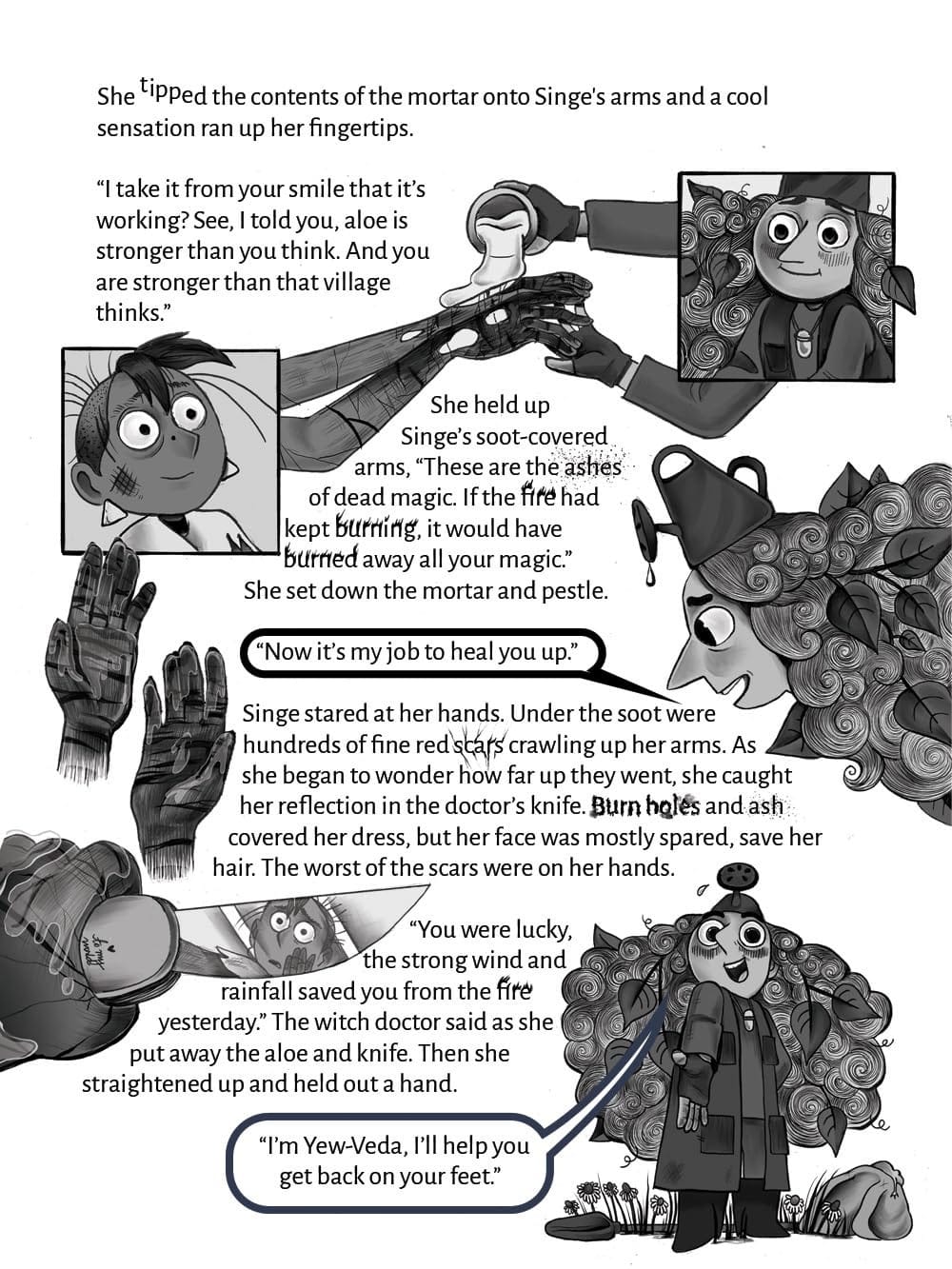

Singe’s recovery is aided by Yew-Veda, a healer who was herself nearly burned, and Bufo, a witch trapped in the form of a toad. Together, they navigate a landscape populated by literal demons named Disgust, Doubt, and Despair. These antagonists are not slain by swords, but by the slow, often frustrating process of rest. Here, Dhaliwal subverts the traditional hero’s journey. Singe does not regain her power by pushing harder; she regains it by stopping. This creates a meaningful rebuttal to the girlboss narrative that calls for women in the workforce to excessively lean in. A Witch’s Guide to Burning instead argues that the most radical act a woman can perform in a capitalist patriarchy is to rest before she is broken.

Visually, Dhaliwal employs autologlyphs, where words physically enact their meaning: the word "burn" might be engulfed in flames, or "fade" might slowly disappear from the page. This textual disintegration mirrors the cognitive fragmentation of burnout, where the ability to process information and maintain a coherent sense of self dissolves under pressure. It is a visual language that validates the invisible injuries of stress.

Ultimately, A Witch’s Guide to Burning serves as a cautionary tale for a society obsessed with output. It reminds us that "magic"—whether it be art, care, or innovation—is a renewable resource only if we protect the source. By advocating for a culture that values the worker over the work, Dhaliwal’s story is a vital contribution to the dialogue on sustainable living. It urges its readers, especially its women readers, to extinguish the pyres of productivity and recognize that a person’s worth is inherent, not something that must be constantly conjured.

Discover more about Aminder Dhaliwal’s work and A Witch’s Guide to Burning on her website, aminderdhaliwal.com, or through her publisher, Drawn & Quarterly.