There has been a worrying rise of Basquiat copycat artists, or as the internet has dubbed them, “Basquiat Clones”. What's strange about the phenomenon is that even though their works are blatant copies of Basquiat’s pieces, these copycat artists have amassed a dedicated fan base, a follower count that reaches tens of thousands on social media, who are buying their “original” pieces and prints for prices that begin at a “modest” USD 100. They justify their ability to do so by peddling their wares as Basquiat-esque styled paintings, as works that help introduce more people to Basquiat’s own work, while at the same time representing totally different concepts that are unique to themselves as artists.

NYC-based fashion, art and pop culture critic Adame Cross succinctly observed that these copycat artists are often white cis-men whose privileges help support their careers as Basquiat copycat artists, and yet it is also this very privilege that removes them from the right to claim Basquiat's style as their own. What the Basquiat clones are doing is nothing short of appropriation, as his style is a product of his long contemplation and lived experiences of inequality as an African American man. This is why deconstructing the Basquiat Clones phenomenon is relevant to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of Decent Work and Economic Growth and Reduced Inequalities.

Cross explains that Basquiat’s work belongs to an artistic movement called neo-expressionism which began in the USA during the 70s as a reaction to the strict lines and sleek shapes of minimalism. This movement created artists such as Julian Schnabel, Paula Rego and Basquiat himself, whose works used bold colours, rough brushstrokes and emotional intensity to depict recognizable subjects such as the human figure, animals and more. Basquiat’s style in particular was also heavily influenced by punk, an anti-establishment subculture and a music genre that emerged in the mid-1970s. Punk is known for being loud, fast, provocative and DIY (Do It Yourself). It meant that Basquiat rejected the clean-cut look of minimalism and advertised products, quite literally tearing apart symbols of capitalist greed which prey on society's most vulnerable.

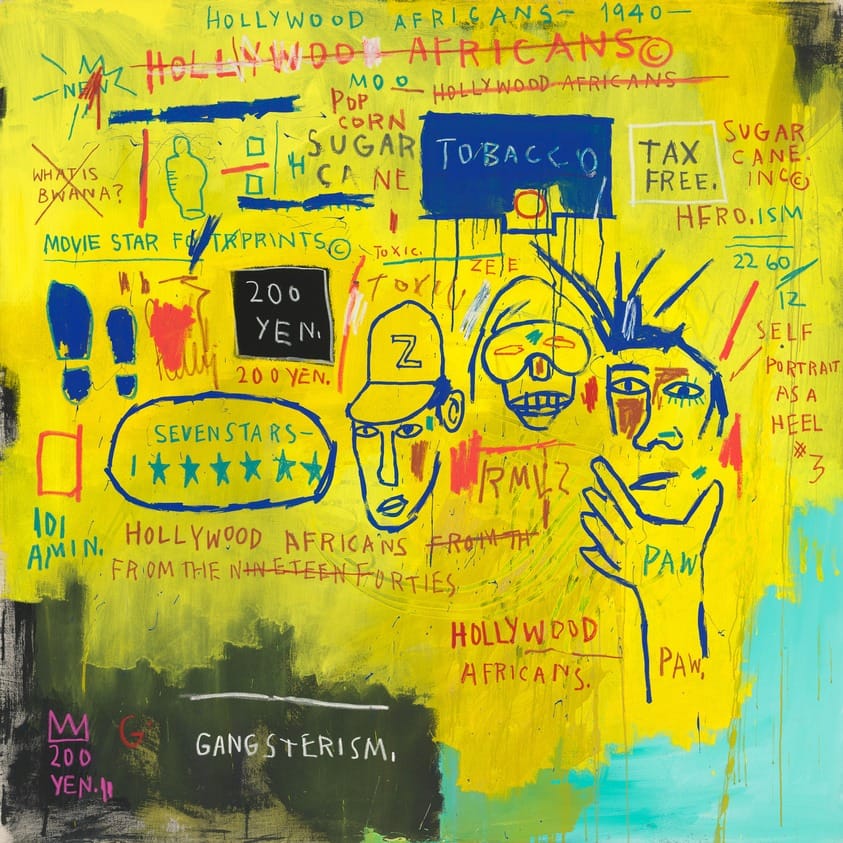

Basquiat, who infamously stated, “I am not a Black artist. I am an artist,” and became the first Black artist to gain international fame, was more than aware of the socio-political and economic discrepancies that Black people in the USA face. Despite not being directly involved in the Black political movements of his time, his pieces, such as Hollywood Africans, which now hangs at the Whitney Museum, openly speaks about how American society discriminates against Black creatives and Black lives.

How then could the followers and collectors of the Basquiat Clones accept and even purchase their works when the artists clearly have not experienced the same racial, economic, and class struggles that Black artists undergo even today? One answer to this strange phenomenon of Basquiat Clones may just lie in today's increasing separation of art from artists, a circumstance that has been greatly aided by recent technological innovations.

One of the most prominent ways that technology has aided the separation of art from artists is through the advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AI) generated art. AI-generated artworks are made by training AIs on different artists’ styles, allowing them to adopt and generate more artworks in those styles despite not having contemplated how these art styles represent specific ideas. This is a process similar to how the Basquiat clones create.

The AI image market, with its speed and efficiency, is projected to be worth over USD 1 billion in 2030, a testimony to its popularity amongst the general public. It can then be argued that people’s familiarity and willingness to create AI-generated art en masse have paved the way for Basquiat clones, normalizing their practice and even allowing it to have a market.

Political anthropologist, Dr Eric Reinhart, argued in his Guardian essay that the trouble with this AI-generated art is that it corrupts the very essence of art-making that makes it an integral part of human life. He writes in the piece, “the belief that, in the act of creating art, one imbues an object with something ineffable from within one’s own being.” According to Reinhart, this then disrupts a viewer’s ability to communicate with the artist through the artworks at a level words cannot access, a process which would have uniquely bridged the gap between one individual and another–an especially crucial process when it comes to conveying the struggles and lives of people who come from marginalized backgrounds.

The rise of the Basquiat clones is more than a curious art world phenomenon. It is a sinister symptom of a capitalist and technological ecosystem increasingly adept at divorcing style from substance, and art from artist. By reducing Basquiat’s visceral, punk-infused critique of systemic racism into mere aesthetics, these copycats—often privileged white men—are in reality performing a double theft: profiting from his legacy, while at the same time erasing the very struggle that forged it. Ultimately, they expose a painful truth: in the pursuit of profit and convenience, humanity risks not just appropriating a style, but annihilating the empathy and understanding that art alone can forge across the divides of inequality.

Find out more writings by Pia Diamandis and her other initiatives by checking her Instagram @pia_diamandis or website www.linktr.ee/Pia_diamandis.