When we think of Renaissance artworks, we think of the epitome of beauty and artistry laid bare on a canvas, realistic and observational, with layers of translucency that elevate its aesthetic appeal. Works from the Renaissance and throughout history have served as both methodical documents of their time and expressions of artistic beauty, as interpreted by their renowned masters, exploring the intimacies of life through the lens of observational truth. Rarely do works of art convey their commentary through grit and brutality; even in their depictions of violence and war, they are intricately rendered with impeccable artistry, highlighting the glory of war rather than its violent reality.

Indonesian artist Rosit Mulyadi, commonly known as Ocid, employs this portrayal of beauty differently from the Renaissance masters, using intricate paintings as a backdrop for humorous societal commentary rather than presenting it as a primary means of depicting glory. In his exploration of the splendour of Romanticism, Mulyadi intricately explores the true purpose of beauty, how it may serve as both an allure and an ambush, unraveling tension beneath the luminous surface. Mulyadi’s use of irony and appropriation creates visual scenes of beauty and transcendence that serve as a medium for the message, often overlooked when focusing on the gold, glory, and glamour of everyday life. Rosit Mulyadi’s cultural commentary, underpinned by artwork reminiscent of Renaissance masters, relates to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of Reduced Inequalities and Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

Born into a conservative, religious family in Java, Mulyadi spent years at an Islamic boarding school, where his first engagement with the arts came through Arabic calligraphy. Unlike his friends and peers, who continued to pursue religious studies, he decided to follow the arts after religious schooling, continuing his studies at ISI Yogyakarta, where he majored in painting. His portfolio of work features explorations of commentary, censorship, and artistic appropriation that convey nuanced sociopolitical messages, ever-present even early in his professional career.

In his first solo exhibition in 2012, titled “(k)Now” at the Ministry of Coffee, Yogyakarta, art observer Hendra Himawan says that “the story Rosit brings in his work is a world that worships materialism, which draws all relationships, interests, and orientations to the material movement of objects.” He states, “The entire story voiced by Rosit is not merely a portrait of complaints about the chaos of the world, but quite the opposite. Through his works, Rosit wants to instill positive conviction and spirit that it's never too late to start making changes.” Mulyadi’s work explores the works of Western master painters, distorting their original meanings to create a new context in his pieces.

Mulyadi’s latest solo exhibition with Gajah Gallery, titled “Humans, After Centuries,” showcases a pivotal moment in the artist’s career where he revisits an era in Western art history to portray an inquiry into beliefs, beauty, and the paradoxes of desire. OCULA writes in their press release of the exhibition that “Mulyadi offers a deeply personal yet timely reflection on what it means to be humans after centuries of inherited images, ideals, and prohibitions.” In his featured works, like Malam Jahanam di Depan Rumah (A Cursed Night in Front of the House) (2025), he emulates Francisco de Goya’s The Third of May 1808 in Madrid to showcase the harrowing political landscape of Indonesia and the fragility of its power, creating a mirror to Goya’s portrayal of civil war in the modern war for political justice. Mulyadi portrays the circular nature of violence through the piece and its attribution to Goya, as, despite the tranquillity of life portrayed in popular mainstream media, violence will always recur, while resistance flickers. Inequality will often persist in worlds where those in power remain unchecked, and Mulyadi’s harrowing reconstruction of Goya’s piece lays bare the realities of the often violent struggle for equality and justice.

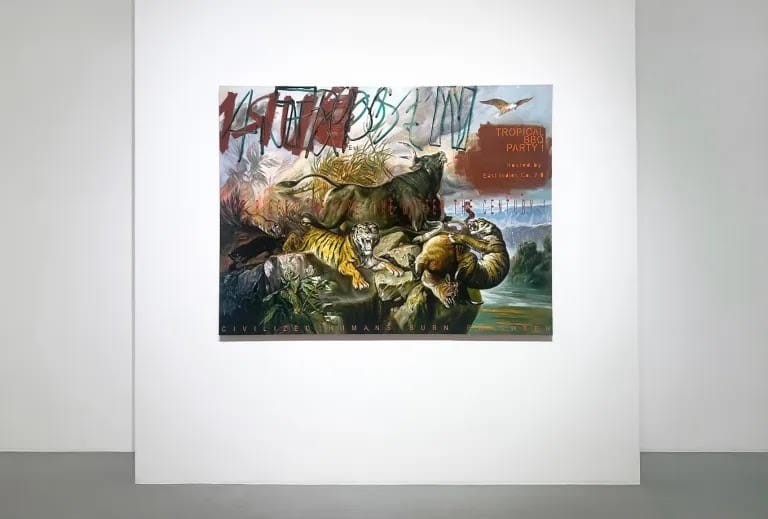

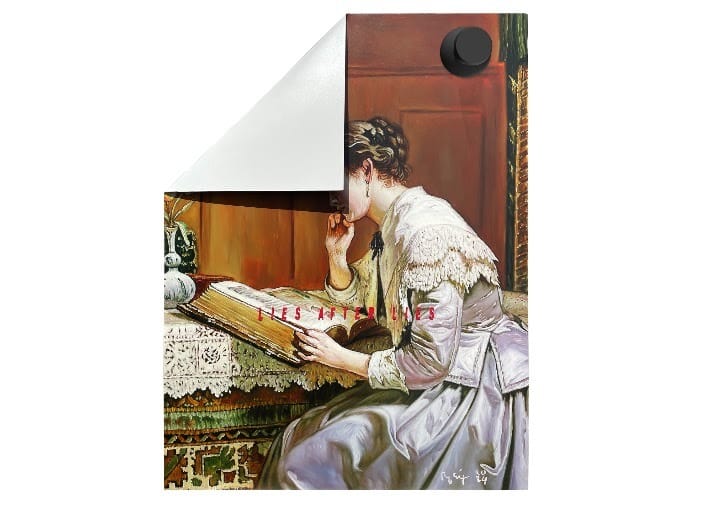

Furthermore, Mulyadi’s interesting use of censorship and commentary creates a powerful commentary on the world's current sociopolitical landscape. In an era of pristine, curated imagery, he subverts the notion of perfection by adding partial censorship and commentary. He uses bold colours and lettering to create contrast between the beauty of the painting and the stark commentary within the text. This is evident in his works such as Percakapan Tanpa Solusi (Conversation Without a Solution) (2023), Romantic Liar (Pembohong Romantis) (2023), and Skeptis #1 (2024). The works are blurred, folded over, and covered in text, reminiscent of vandalism yet poetic in that they convey an important message about reflections on life and its injustices. This idea is showcased candidly in Useless Negotiation (UN) (2025), where the subject is partially covered with a stark, contrasting white square with the words ‘My Lipstick Negotiates Better than The UN’; a tongue-in-cheek commentary on how the United Nations can be inefficient in negotiations for important matters, like the Ceasefire of Palestine or the Russian occupation of the Ukraine.

Political commentary has always been a part of the artistic landscape. Artists like Eko Nugroho, Arahmaiani, Heri Dono, and Dadang Christianto have utilized political landscapes and sociopolitical commentary as the main backdrop of their work. With the rise of Soeharto’s New Order regime in 1965, banning the Institute of People’s Culture of Indonesia, artists associated with left-wing politics were often imprisoned, killed, or forced into exile, leading to a climate of fear of opposing popular opinion in the political landscape and underground abstraction. Artworks that commented on or criticized the government were banned, artists and journalists were silenced, and artworks began to focus on safer subjects like landscapes and portraits.

The political criticism landscape in Indonesia has shifted back to the age of Soeharto’s New Order. New laws effective on January 2nd, 2026, have reinstated penalties for imprisoning people who attack the honour or dignity of the President and/or Vice President, as rooted in the 1915 Dutch Colonial Criminal Code. The reinstatement of the colonial-era law, cancelled by a constitutional court ruling in 2006, caused controversy, as many civil groups feel it imposes oppressive censorship on freedom of speech merely for offending the president as a civil servant. It begs the question: what makes the president so special that they can imprison someone for feeling insulted by criticism?

The silencing of artists, however, had happened before the reinstatement of the insult clause law. In 2024, the National Gallery of Indonesia cancelled artist Yos Suprapto’s solo exhibition at the last minute due to alleged ‘insulting portrayals of President Joko Widodo.’ Censorship of sociopolitical criticism within the arts is becoming rampant as the apparent image and honour of political figures trumps the voices of the people who appoint them. As the future of political commentary within the Indonesian arts grows bleaker, it is refreshing to see emerging artists like Rosit Mulyadi continue his practice of satirical sociopolitical criticism atop portrayals of what can be seen as ‘safe’ subject matter.

The arts are an important vehicle for showcasing the voices of the people and for documenting a period in time when citizens are controlled, manipulated, and mistreated by those whose job is to protect them. Rosit Mulyadi’s works combine the beauty and romanticism of 18th- to 19th-century artworks with poignant commentary on global sociopolitical issues. His works underscore the importance of art in amplifying the voices of the voiceless, combining aesthetic beauty and intriguing commentary to create layered masterworks with extraordinary meaning.