In the halls of the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris, surrounded by antique taxidermy and hunting rifles, a different kind of carcass hangs from a hook. At first glance, it appears to be the side of beef—raw, red and visceral. But step closer, and the illusion of violence gives way to an unexpected intimacy. The "muscle" is floral cotton, the "fat" is white linen, and the "bone" is terry cloth. This is the work of Tamara Kostianovsky, an Argentine-American artist who is redefining the boundaries of sculpture by transforming discarded clothing into hyper-realistic, often unsettling depictions of nature and mortality.

Kostianovsky’s exhibition, The Flesh of the World, showcases her signature aesthetic: a meticulous "butchery" of textiles that turns the soft debris of everyday closets into hard questions around human consumption. Her choice of material is both an act of recycling and a political confrontation on the relationship between humanity and Mother Nature today. She uses old t-shirts, sheets and towels—materials that once touched the human body to replicate the "flesh" of the earth to create animals and plants, both dead and alive. This allows her to remind people to be more aware of how their clothing and larger consumption habits have affected the world around them, aligning her practice with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of Responsible Consumption and Production and Life on Land.

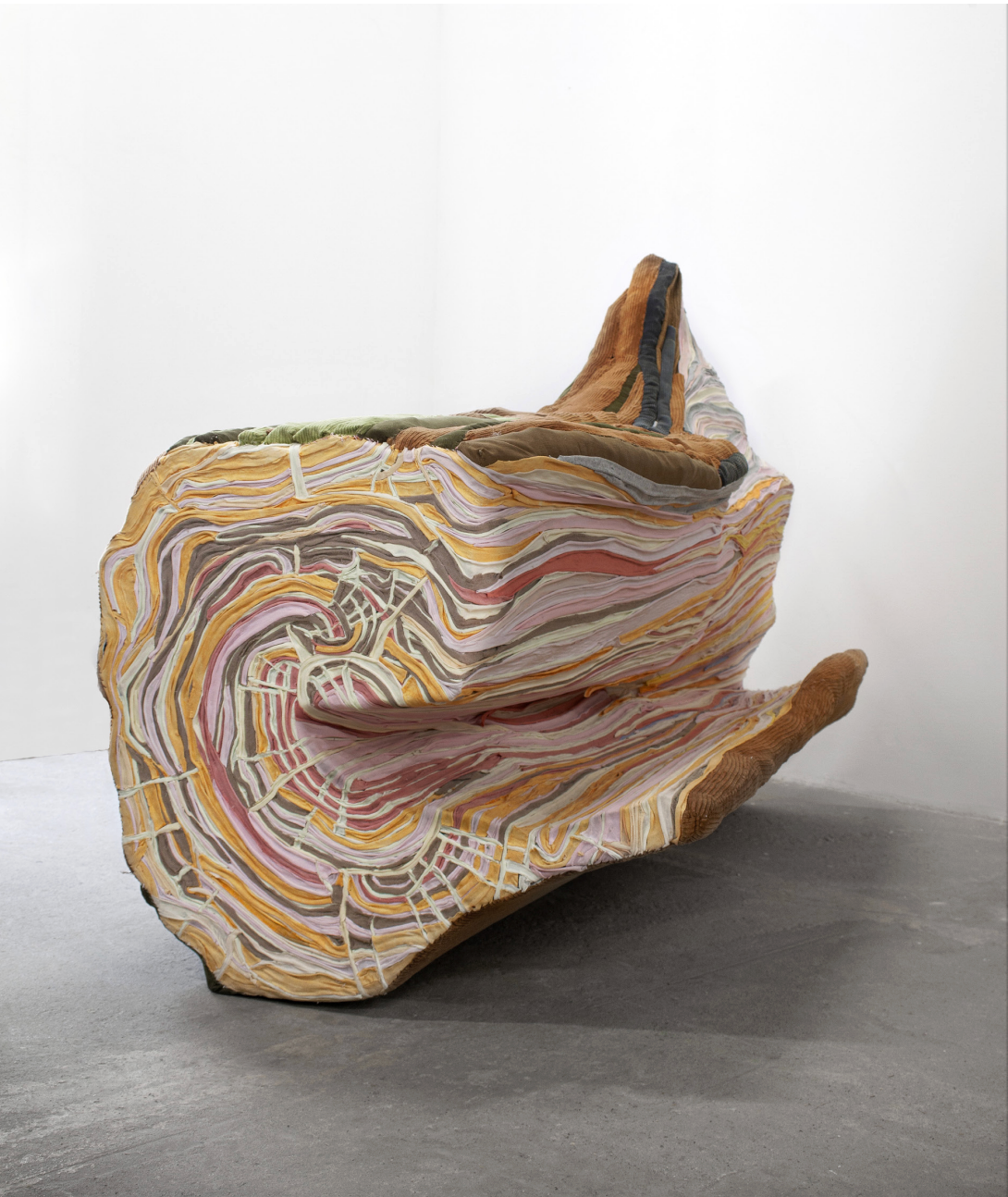

The artist’s fascination with "soft" sculpture stems from a desire to address violence enacted towards the planet without perpetuating it. Growing up in Argentina, Kostianovsky was exposed to the visual language of meat consumption, a central part of the local food culture. She then uses her work to navigate the intricacies of this very personal sense of ecological grief, where she feels like a part of her identity is fighting with another. Take, for example, her series of severed tree stumps, crafted from the garments of her late father; they serve as memorials to both the world’s rampant deforestation and her loss of her father. The tree stumps suggest that real environmental change will only come if the loss of the Amazon or the burning of the Californian coast were handled not just as mere statistics, but as a personal loss, as intimate as the loss of a family member.

Critics, such as those at Art in America, have noted that Kostianovsky’s work also operates on a logic of "metamorphosis." In her hands, sites of carnage become matrices for new life. These range from the open wounds of her fabric carcasses to vibrant tropical birds, often stitched from neon sportswear and patterned silk. This imagery suggests that nature is resilient, but it also implicates the viewer. The beauty of the birds is inextricably linked to the waste from which they are made.

This duality forces the viewer to confront their complicity in global waste. They themselves are the consumers who buy the cheap clothes that eventually choke landfills; they are the ones who demand the cheap beef that drives deforestation. Kostianovsky takes this guilt and stitches it into something undeniable. As she explains in interviews with Audubon and CanvasRebel, her goal is not to shame, but to reveal the "scars" people have created—both on the planet and on themselves.

Ultimately, Tamara Kostianovsky’s work is a form of healing. It proposes that we cannot fix the world by looking away from the damage. Instead, we must look at the wound, touch it, and understand what it is made of. In her soft, stitched sculptures, we find a brutal but necessary truth: the fabric of the world is torn, and it is up to us to mend it.

Discover more of Kostianovsky’s textile transformations on her Instagram or website tamarakostianovsky.com.