In traditional cinematic and art-historical canon, a woman’s body was often relegated to a site of passive beauty or, conversely, a source of primal dread. Barbara Creed, in her seminal work The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, argues that when women are depicted as monstrous, it is frequently linked to their biological functions—giving birth, menstruation and more that a patriarchal society sees as horrendous. However, Balinese artist Umah Yuma is part of a rising group of artists who see feminine "monstrosities" as not a source of shame, but a potent site of reclamation. Her work embraces the visceral, the surreal and the overtly biological quality of a woman’s monstrous side, allowing her to dismantle the restrictive aesthetic discipline of beauty that history has placed upon women as an artwork’s subject. This is why her work is aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of Gender Equality and Reduced Inequalities.

Central to Creed’s thesis is the figure of "Archaic Mother," a prototype of the monstrous-feminine that represents the female reproductive body as a terrifying, all-encompassing force. In patriarchal horror, this figure is often depicted as a "monstrous womb" which undergoes an unholy "bloody birth," a site of abjection that must be expelled or destroyed to maintain the symbolic order. Creed notes that this fear of the feminine often stems from a fear of the generative power of the female body—seeing the grotesque ability it has to give life that, by extension, can also take it away.

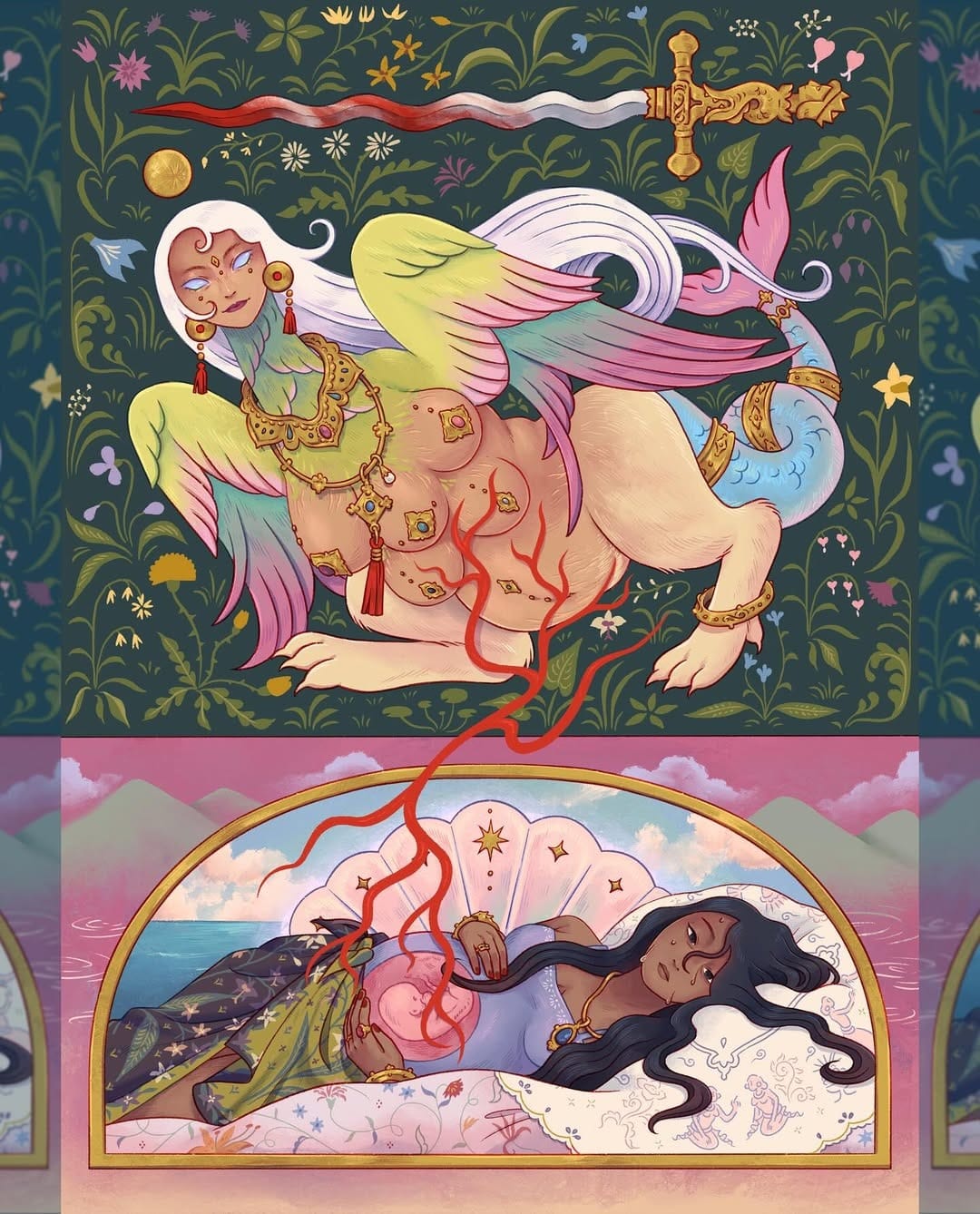

Umah Yuma’s practice engages directly with this archaic energy. Her visual language is rich with organic textures that resemble skin, internal organs and fluids, collapsing the boundary between the internal and external. Yet, where traditional horror films used these images to evoke revulsion, Yuma uses them to evoke awe and agency. In her work, the womb is not a site of horror but a site of sovereignty. Her work makes the internal physical reality of the female experience undeniable, forcing viewers to confront the very biological essence that society often seeks to sanitize or hide behind “civilized” notions of femininity, which white washes and shaves them clean.

One of the most potent faces of the monstrous-feminine identified by Creed is the vagina dentata—the "toothed vagina"—which embodies the patriarchal fear of women as “the castrator". Creed argues that this myth shifts the source of terror from the male's own vulnerability onto the female's "dangerous" anatomy. In mainstream media, this motif is used to justify the containment or punishment of the female character.

Yuma, however, reclaims the vagina dentata and other motifs of bodily threat, transforming them from symbols of male anxiety into metaphors for female self-defence and autonomy. In pieces such as Ibu, these "monstrous" features are presented as defensive fortifications—tools for a body that refuses to be violated or possessed. This artistic choice is a radical act of gender equality; it rejects the role of the woman as a passive victim and instead portrays her as a being capable of exerting power through her own physical existence. By leaning into the "frightening" aspects of femininity, Yuma dismantles the male gaze that seeks to categorize the woman-as-object, insisting instead on the woman-as-subject.

The concept of "abjection," popularized by Julia Kristeva and heavily utilized by Creed, refers to that which "disturbs identity, system, order". It is the skin on the milk, the corpse or the bodily fluid—things that blur the line between the self and the other. Creed points out that the monstrous-feminine is often abject because it exists at the boundary of life and death or the boundary of the clean and the unclean.

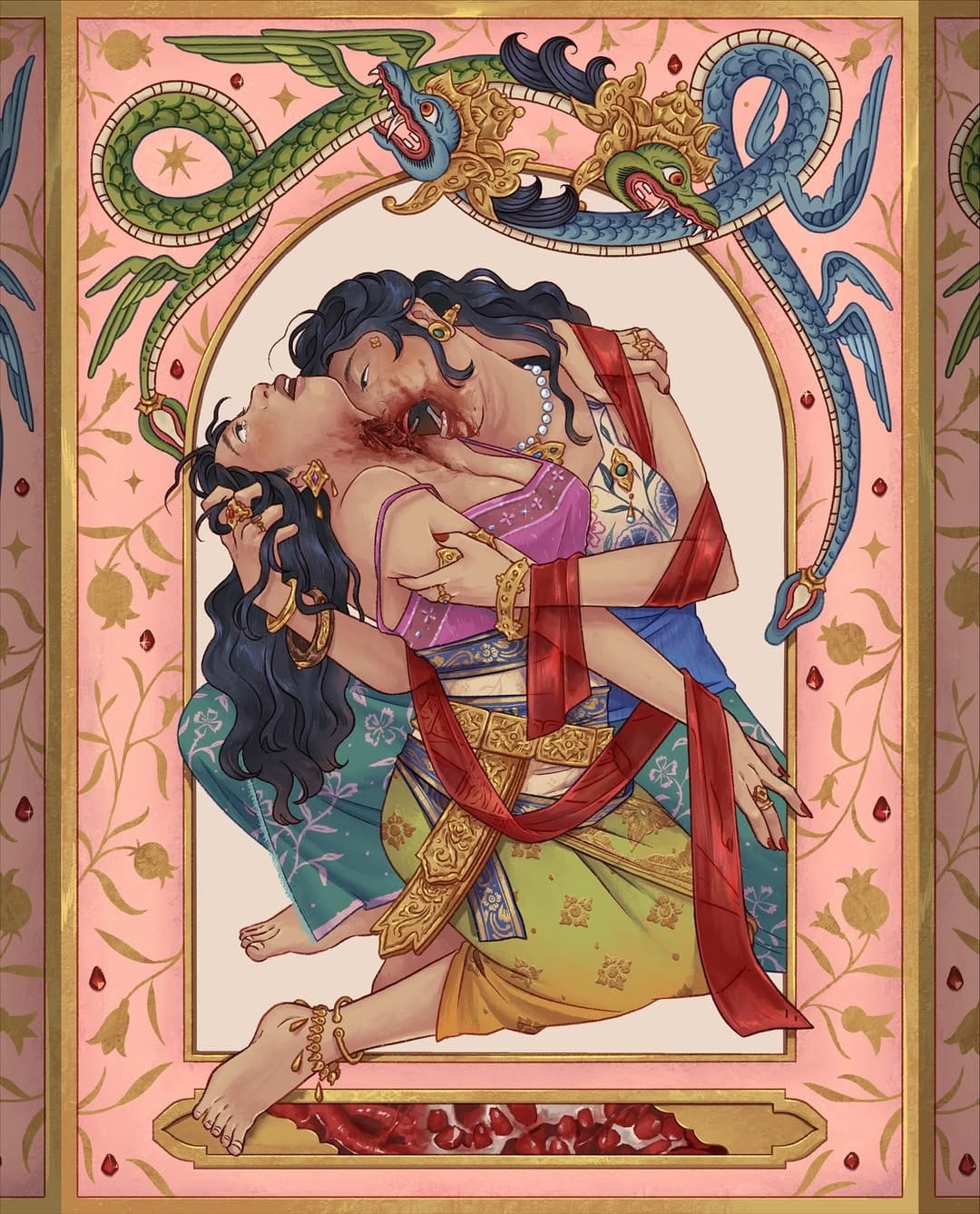

Yuma’s work also often utilizes the aesthetics of the abject; in one piece, two women are seen locked in an embrace, while one bites the throat of the other, revealing her internal organs. This use of visceral, wet-looking materials and pulsative, dark environments creates a space where the audience is "swallowed" into a feminine interiority. It creates a psychological tension that mirrors the experience of the abject. However, rather than leading to an "expulsion" of the feminine, Yuma’s work invites an "immersion." She argues that the abject parts of the female experience—menstruation, childbirth and the raw physicality of the body—are not "waste" to be hidden, but essential truths to be integrated. By bringing these themes into the public’s eye, she challenges the systemic silencing of women’s bodily narratives, providing a counter-discourse to the patriarchal structures that have historically controlled female reproductive rights.

In The Monstrous-Feminine, Creed also discusses the "possessed body"—a woman whose physical form is taken over by an external, often demonic, force. This trope serves to suggest that women are inherently unstable or prone to irrationality. In the same work we’ve discussed, Yuma subverts this by presenting bodies that seem to be "possessed" only by their own untamable vitality. In other works, her figures often appear in states of transformation, with limbs morphing into roots or organs expanding beyond their traditional confines.

This "self-possession" is a direct answer to the societal demand for women to remain "composed" and "containable." Yuma’s art suggests that a woman’s power is often found in her refusal to be small. The "monstrosity" of her figures is actually an expression of their expansion—a refusal to be restricted by the frame of the canvas or the expectations of the viewer.

Umah Yuma’s art is a vivid reminder that true equality requires the courage to look at the "monstrous" and see it as human. She breaks the mirrors of conventional beauty to reveal a more complex, sovereign truth: that the female body, in all its abject, generative, and "terrifying" glory, is a site of ultimate power. Her work proves that when women reclaim the right to be "monstrous," they finally gain the freedom to be whole. This makes her work a blueprint for a future where gender equality is rooted in the unapologetic celebration of the female self, in all its visceral complexity.

Find out more about Umah Yuma’s work and her exploration of the feminine psyche on her Instagram @umahyuma and Behance @nathayuma.