Plant collecting, for the purpose of research, cultivation or as a hobby, is an ancient practice dating back centuries, with the earliest records appearing in 1495 B.C. Today, the herbarium—a museum of pressed and preserved plant specimens—has become increasingly valuable and has helped scientists gain critical information on climate change. Considering that herbaria were first created in the mid-16th century, their specimens are often old enough to aid in documenting progressive environmental degradation. Plant phenology studies have provided some of the best evidence for large-scale responses to rapid climate change.

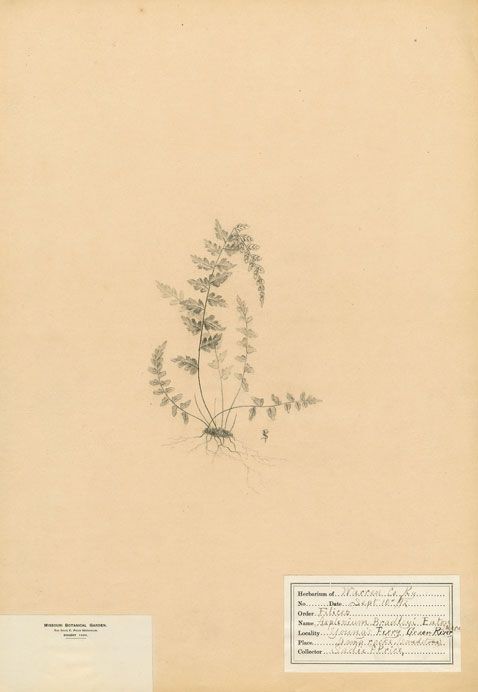

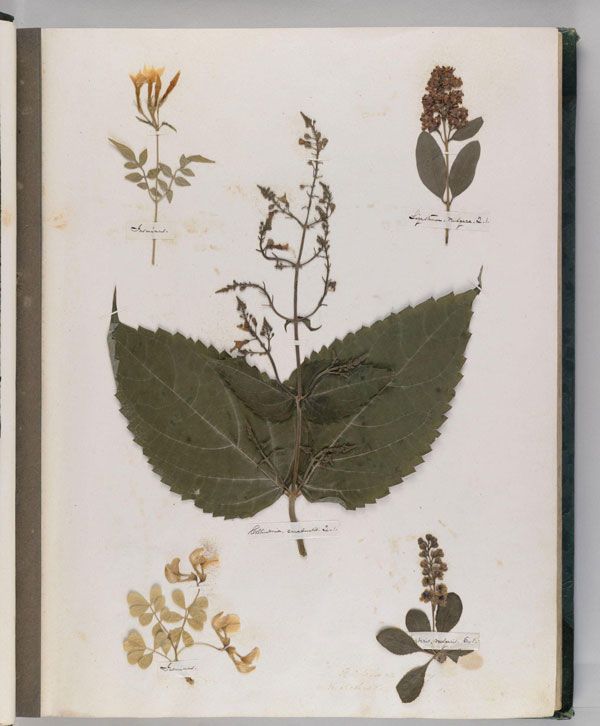

Information on the herbarium sheets (the paper that plants are attached to and where they are identified) has become increasingly digitized and widely available, and thus the importance of these collections is becoming better known not only to scientists, but also to artists, who have long drawn inspiration from them. Not only are the pages of pressed plants aesthetically rich themselves, but herbaria have also been home to an array of “archival” art. There is an interesting kind of interaction between art and science that takes place at the herbarium. This relationship is sometimes physically close, as the sheets are sometimes arranged with accompanying and related artworks.

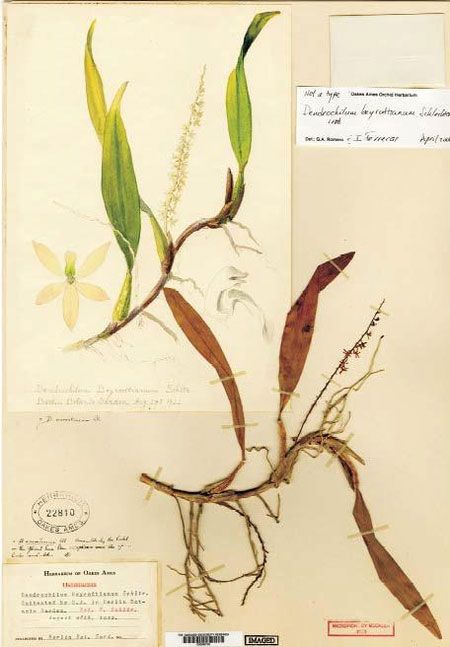

A perfect example of this is in the work of Havard botanist and orchid specialist Oakes Ames (1874-1950). His wife, Blanche Ames, was a multidisciplinary artist and would illustrate her husband's botanical research using watercolour as a complement to the dried specimen, painting it as if it were living. There are plenty of examples of botanical drawings and prints kept in files with the specimens in cabinets in the herbarium—they were treated as scientific works rather than simply works of art. Such art is a case of balance between filtering out the irrelevant and focusing on the essential, as drawing, especially with pen or pencil, is a means of displaying and regulating fine detail that could not be captured otherwise.

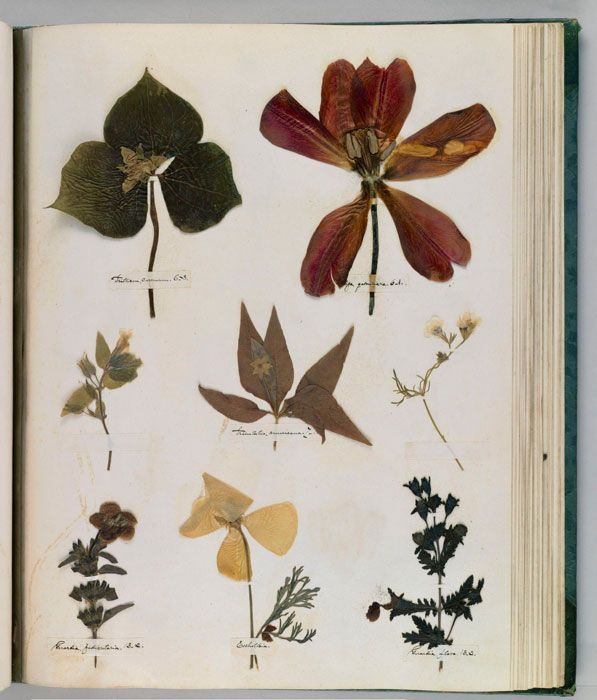

In preservation, the actual plants are often beautifully arranged on pages and have aesthetic as well as scientific significance, making them an important source of inspiration for artists. Presenting a unique position in history, Emily Dickison, one of the leading 19th-century poets, lies at this intersection of science and poetry. Well before she had begun to write poems, Dickinson indulged in a rather distinct but surprisingly parallel art of contemplation and composition: the gathering, cultivation, arranging and pressing of flowers.

Her striking compositions, all displayed in a collection now digitized at the Harvard Library, often juxtaposed botanical specimens that in the wild would not ordinarily occur together. Some say her arrangements were poetic, for instance, the first page where she combined jasmine and pivot, positioning them in the center of the page so that they resembled a single plant. It has been argued that Dickinson’s expertise in botany and gardening profoundly shaped her poetry, as she often wove botanical elements into her writing, combining her passion for literature with her passion for nature (see: May-Flower, With a Flower and Nobody Knows This Little Rose).

Today, artists continue to be inspired by these archives. Canadian painter, Karen Yurkovich, centers her art around botanical imagery and explores our complex relationship with nature. Her pieces include themes such as native and immigrant plants, issues of biodiversity and the symbolic role of plants within different cultures. In a project and exhibition with the Beaty Biodiversity Museum in Vancouver called “The Herbarium Project”, she made pieces that create new taxonomies or classifications based on the cultural and historical narratives of the plants. Each work blends indigenous varieties with foreign ones, forming new relationships among them.

In a Project called “Natives and Immigrants”, Yurkovich forms explorations of what she describes to be the “movements of people (who bring plants as a memory of places they have left to put down roots in a new place) and movements of nature (vegetative life as a constantly adjusting territory to climate changes and human desire).” These works see herbaria as offering an opportunity to travel through time—a way to discover what once was and explore what can be.

This is what Helen Humphreys describes in her book, Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium, a fascinating plunge into the world of botany and the introspection that she derived from these archives. Spending a year at her local herbarium as if it were real wilderness and discovering mysteries hidden in its samples, she develops reflections on life, loss and the importance of finding solace in nature. Her passages on loss and climate change were particularly compelling. One of my most striking and fascinating personal findings in this book was the particular fact that herbaria are first-hand witnesses to climate change.

Just as they can be used as time machines into the past, they are a glimpse also into the future. Because plants are sessile, in other words, immobile or permanently attached to the earth, they are particularly vulnerable to environmental change. The evolution over time of many of their responses to environmental change is preserved in herbarium specimens, which therefore provide unique data for the study of global change.

Through the resources presented by herbaria, artists and scientists alike are calling for the conservation of biological diversity, as well as for the "protection, restoration and promotion of the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems,” part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for Life on Land. The herbarium is a place where the relationship between art and science flourishes, offering century-old botanical artwork, sources of inspiration to artists, and significantly, valuable research on the effects of climate change on biodiversity.

See more of Karen Yurkovich at karenyurkovich.com.

You can also find Helen Humphreys's book, Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium here.