The artist is an integral part of interpreting art. Their lives clue viewers into representative symbols, emotions, and meanings. With Chaim Soutine, however, one does not have the luxury of knowing the artist. The life of this early 20th-century Expressionist is little more than a myth or legend. The details of his life are mostly unknown, with the only known stories of his life uncertain in truth. Yet, the mysteries surrounding Soutine only serve to make his work more intriguing. Without the confines of context, Chaim Soutine’s work transcends his initial intentions and dives towards subjectivity.

Born in 1893 to a Jewish family in Russia, Soutine lived much of his life in miserable poverty, leaving a shadow on his work until his last brushstroke. Soutine’s life truly started at the age of twenty when he moved to Paris to pursue his career as an artist, only finding moderate success in 1922 when American modern art collector, Albert Barnes discovered his work, buying approximately 50 pieces on the spot.

It is clear why Soutine’s work garnered attention at such an early age. The artist had the rare and gifted ability to infuse life into any canvas he touched. From the twisted landscapes and caricatured portraits to his endless, almost obsessive works on food and death, Soutine brought a unique voice to the Expressionist movement.

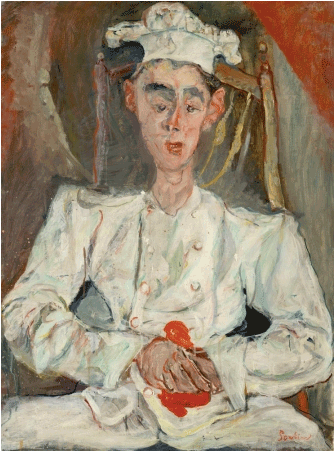

Soutine’s portraits of everyday people feel closer to reality than any realist painting. Soutine painted his subjects as caricatures, verging on mockery and humour, yet somehow still capturing human despair. The Little Pastry Cook is a brilliant example of how Soutine could evoke his subject’s personality by prioritizing their internal feelings rather than accuracy in their physical depiction and allowing emotion to ooze from the canvas through the vibrant colours and distorted shapes.

It is Soutine’s still lifes, however, that received the most praise, particularly Carcass of Beef (inspired by Rembrandt’s The Flayed Ox (1655) which Soutine spent hours contemplating in the Louvre). Soutine obsessed over food, death, and their relationship. One of the only known quotes from Soutine describes this fascination: “Once I saw the village butcher slice the neck of a bird and drain the blood out of it. I wanted to cry out, but his joyful expression caught the sound in my throat… This cry I always feel it there… When I painted the beef carcass it was still this cry that I wanted to liberate. I have still not succeeded.” Carcass of Beef, along with his other still lifes depicting food and death, reveal a more grotesque and violent side to the artist. They are infused with deep colours, most notably reds and blues, along with lingering darkness present in both his works and life. Using a real beef carcass hanging in his studio as his subject, Soutine would frequently brush the carcass with blood from a local butcher to keep the colours alive. While fighting off flies and angry neighbours, who supposedly called the police due to the horrid smell, Soutine managed to create what is referred to as his greatest masterpiece. However, this story is only one of many on how Carcass of Beef came to be. In another, the blood from the carcass dripped through the floorboards of his studio, causing his downstairs neighbour to fear that he had been murdered; yet none of these accounts of the creation of Carcass of Beef can be confirmed. The details of Soutine’s personal life remain a mystery as the only information on him has been passed down by word of mouth, told, and retold until all that remains is vague, often contradictory statements. However, his paintings speak for themselves. His expressionistic style allows us to peer into not only his life but his mind.

Though his still lifes are considered his most significant achievements, Soutine’s landscapes are astonishing. Looking at his landscapes, it is clear that Soutine is allowing viewers to see the strange places not as they were, but as Soutine himself saw them. The eye can barely piece together the almost formless paintings ranging from dreamlike to nightmarish, yet they are strangely moving. The impasto application of paint seen in Vue De Céret creates a sense of movement, with the agitated brushstrokes evoking naturalistic energy unique to Soutine’s landscapes.

Without much of the artist’s history and the stories behind each of his paintings left untold, Soutine’s art becomes a surprisingly personal experience. It is not Soutine’s life viewers see as they peer into the rich whirls of colour, but their very own. One has no choice but to separate the artist’s art because, in truth, no one knows the artist in entirety, giving viewers the rare freedom to interpret his works without any influence and impose personal meaning.

As a Jewish man, Soutine spent the last years of his life inexhaustibly hiding from Nazis when the Germans invaded Paris in the summer of 1940, dying three years later of a stomach ulcer at the age of 50. Much like his art, Soutine’s life reads like an uncertain painting: obscure of meaning and mysterious in truth, interpreted and imagined through the eyes of many, but the only one who truly understands it is Chaim Soutine himself. His work speaks for him in the way the written accounts of his life history fail to capture. Soutine is remembered through his art and his art alone. Certainly, we’ll never know the true-life story of Soutine, but perhaps it’s better that we can look at the life he chose to share through his paintings and see the truth from his perspective.