The well-known radicalist of the 20th century, Diane Arbus dedicated her independent photography career to representing marginalized communities and shed light on the lives of underrepresented people. As a person whose “favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been,” Arbus didn’t shy away from photographing the unexpected, and was instead enthralled by it, redefining portraiture in the process.

After spending the better part of a decade as a fashion photographer with her husband, Arbus grew tired of the unfulfilling commercial work. With the support from her husband, Arbus replaced the small photography studio with New York City in the 1950s, a city bursting with diversity and artistic potential. In her early works, exemplified by Man With A Curious Baby On The Subway (1956), Arbus slyly stole moments from unsuspecting subjects, yet her hallmark documentary style is still present, watching people of all kinds with an objective eye, observing life as it unfolds and capturing its essence. These earlier photographs reveal her initial aversion to human contact, shooting wax museum displays, movie screens, the streets of Coney Island, and the occasional person from afar. In these works, if ever a person eyes the camera, it is with an unknowing look of surprise. However, as her works evolve her subjects begin to knowingly face the camera, her photographs become almost provocative with vulnerability. Her subjects are emotionally exposed to the point of nakedness, their eyes staring directly into the camera. With this ability to break down the walls of her subjects, Arbus Peels back the veil of New York City, its humanity, and its idealized version of normality to uncover the true beauty of humanity which does not lie in conformity, but variation.

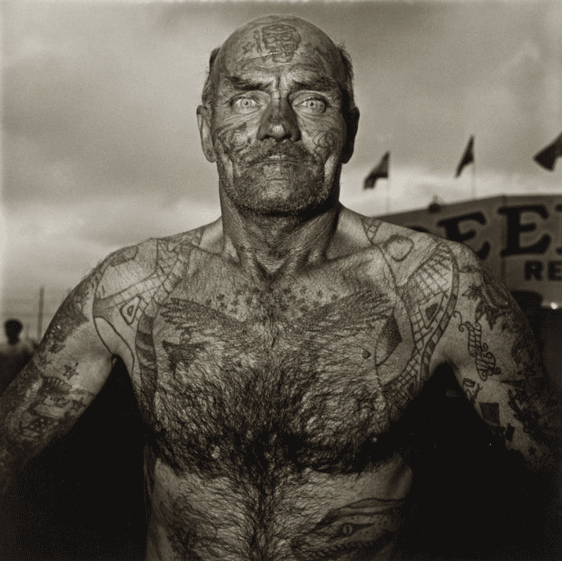

Arbus strived to shed light on the unconventional, those who most photographers turned a blind eye to. Arbus doesn't showcase their abnormalities, but their common humanity. In her intimate black and white portraits, her subjects, dressed in their societal roles, are stripped of such labels. In Tattooed Man At Carnival (1970), a circus performer stands in front of the circus, nearly erasing it from the foreground. His overpowering presence demands the viewer to see him—not as a circus performer, but as a person. As with most of Arbus’s work, Tattooed Man At Carnival is almost uncomfortably confrontational as the eyes of her subject pierce the viewer’s preconceived judgements.

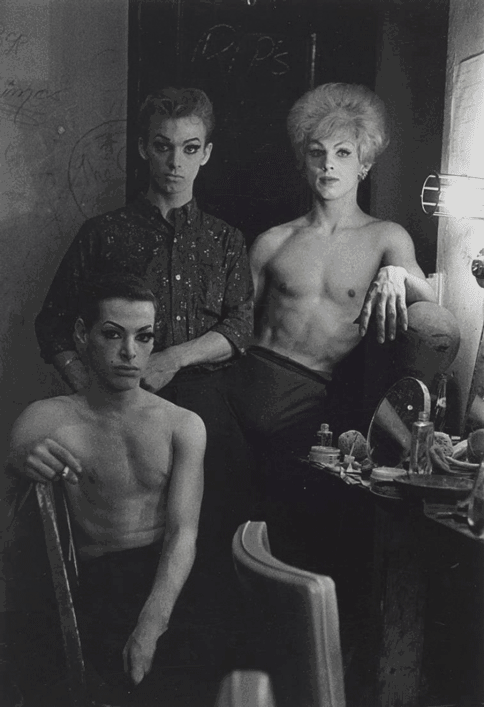

Diane Arbus had a career-long fascination with the relationship between gender and identity, a fascination expressed in her numerous works capturing drag queens in the process of transforming themselves into their female personas. These portraits blur the lines of gender by contrasting traditionally masculine and feminine features. In Three female impersonators (1962) and A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street (1966), her subjects pose with a proud vulnerability. Not unlike most work, her portraits of drag queens expose the humanity of those who reside on the outside of normality. In a time where their profession and identity were only narrowly accepted, Arbus intimately showcased their nonconformity alongside their humanity, allowing the viewer to see bits of themselves in those they may consider most different.

Triplets In Their Bedroom (1963) further explores Arbus’s interest in the concept of identity. The photograph shows three triplets in the middle of three identical beds, wearing three identical outfits. The siblings are indistinguishable from each other if not for their separate facial expressions that read: wise, happy, sad. Here, Arbus seems to depict an individual with three elements of themselves, acknowledging conflicting identities within oneself and physically depicting the mind’s divides.

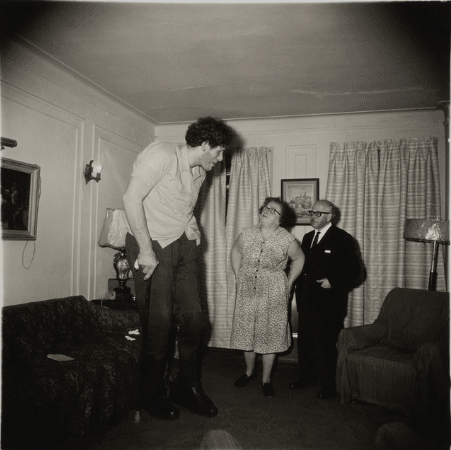

Arbus often photographed people in their homes. This tactic lent a feeling of intrusion, evident in works such as Jewish giant at home with his parents in the Bronx (1970). The iconic photo pictures Eddie Carmel, whose height was a result of a rare medical condition known as gigantism, with his parents. In discussing the photo, Arbus said, "You know how every mother has nightmares when she's pregnant that her baby will be born a monster? I think I got that in the mother's face." With quotes like this, it is unclear whether Arbus wanted to rightly represent those who have been excluded from society or to exploit them to further her own artistic agenda. Although her use of words such as “monsters” may be a consequence of her time’s conditioning and relegation to those who are anything other than the norm as “freaks,” in referencing her work, Arbus often holds a disrespect towards her subjects, contradicting the respectful eye of her camera.

Regardless of Arbus’s intentions in photographing those who lead unconventional lives, her work undoubtedly contributed to creating a future that embraced difference in whichever form it may present itself. Although her unorthodox and ultimately tragic life often eclipses her work, In capturing what few photographers before her had, Arbus forever transformed the landscape of photography by capturing the “things which nobody would see unless I photographed them."