The counterintuitive attraction to horror media is a phenomenon not easily explained. Naturally, conventional interpretations of aesthetics would delineate that pleasant imagery triggers a reward response in the brain – images of things that create pleasure in life act as a stimulant for the production of dopamine, causing one to experience feelings of happiness as a result of merely looking at these images. This reaction may lead one to assume that perceiving images which cause negative responses in the brain, that illicit painful or fearful reactions in life, should be avoided entirely. The appeal of horror is a paradoxical one and the study of which is more nuanced than that of any other genre. Contemporary scholarship of horror in media leans heavily towards the study of film and television, as the perennially lucrative horror genre in cinema keeps it at the fore in popular culture.

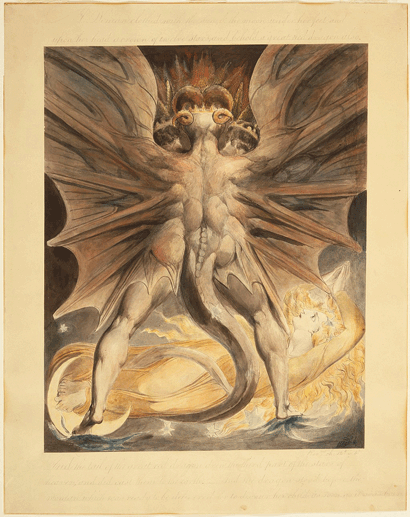

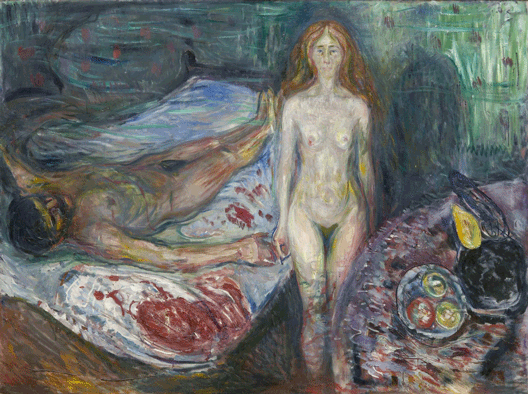

Horror in visual art, less prevalent in mass media, is evident on a much longer timeline and has produced some of the most indelible images associated with the genre. Regardless of the medium, the message of horror art consistently reflects collective anxiety or social fear that arises when fundamental knowledge comes into question. Horror is meant to evoke fear, shock, and disgust, usually in sympathy with the subject; these feelings or emotions are provoked by monstrous figures or disturbances in the natural order. The answer, however, to why people continuously gravitate towards images that should evoke these feelings is not as easily defined as the genre itself.

Pain and Punishment

From an existential standpoint, the appeal of gruesome imagery can be explained by the need to identify the reality of danger and suffering as integral to the human condition. Contemporary philosopher and art and film historian Noel Carroll’s fundamental work, The Philosophy of Horror (1990) described a basis for why viewers should seek out the horrific image in art. He argues that the crux of our relationship with violent imagery lies in the desire to feel sensation, specifically, negative sensations such as fear and unease through the safety of detachment. We are in a way experiencing the pain and suffering incited by the content of the horrific image, but without any true physical threat to ourselves.

Regarding the viewing of violent punishment of a person or character in art, psychologist Marvin Zuckerman noted a correlation between the enjoyment of such images and the tendency to seek out feelings of intensity through the simulated experience of danger, i.e. roller coasters, bungee jumping, skydiving. This type of enjoyment when viewing a subject in torment is typically predicated on the Dispositional Alignment Theory, which states that the level of cathartic enjoyment from viewing the punishment of a fictional character is in direct relation to the level of disdain one holds for that character. In other words, if the person is perceived to be deserving of their punishment, the viewer will experience a positive reaction when confronted with a visual manifestation. Conversely, the witnessing of punishment inflicted on someone who is not perceived as deserving creates a deeper and more esoteric sense of attraction for the viewer. This type of viewing suggests a need to empathize with a victim in pain, to safely experience the injustice of their suffering through dramatic catharsis.

A Cathartic Experience

The idea of catharsis – its etymology stemming from the Greek, katharsis, meaning purification – was originally described by Aristotle, who posited that we are inclined to purge or cleanse ourselves of negative emotions through viewing images of pain or the abject in art. The mental and emotional effects of witnessing the depiction of tragedy form a vessel from which to release these anxieties, and the release creates a satiating experience.

Contrary to the Dispositional Alignment Theory, in which viewers achieve positive sensations by viewing the punishment of those seen as deserving, there exists the Problem Watcher, as described by professor of communications Dr. Deirdre Johnston. The Problem Watcher is characterized by a person who seeks out horror imagery for the negative emotional reaction one experiences while viewing the punishment or harm done to those perceived as undeserving. This viewer empathizes with the subject and usually imparts their own feelings of fear, sadness, or helplessness onto the subject.

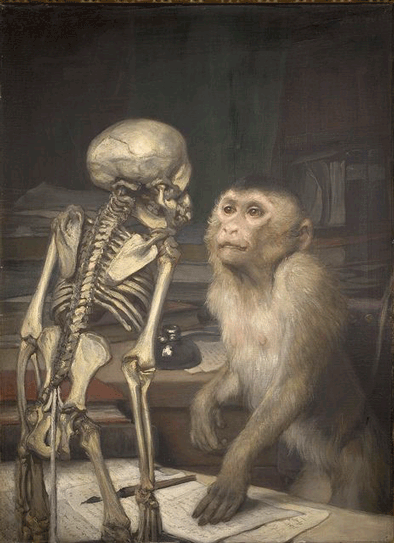

The experience of empathy can be attributed to mirror neurons, as defined in a study spearheaded by psychobiologist Vittorio Gallese; the study was designed to map the premotor cortex in the brains of macaque monkeys in order to investigate embodied simulation. The researchers discovered that the same motor neurons would fire in the monkeys’ brains when they performed an action as did when they witnessed that action being performed by another monkey. The study lends itself to the scientific credence to the cryptic experience of empathy but does not necessarily explain our need or desire to elicit a negative empathetic response through art. The Jungian understanding of the Self, or the quest to know the Self can be applied here.

Coming up in Part II: Jungian theory and two of the most famous horror art paintings of all time.