What is Digital Information, and How is it Collected?

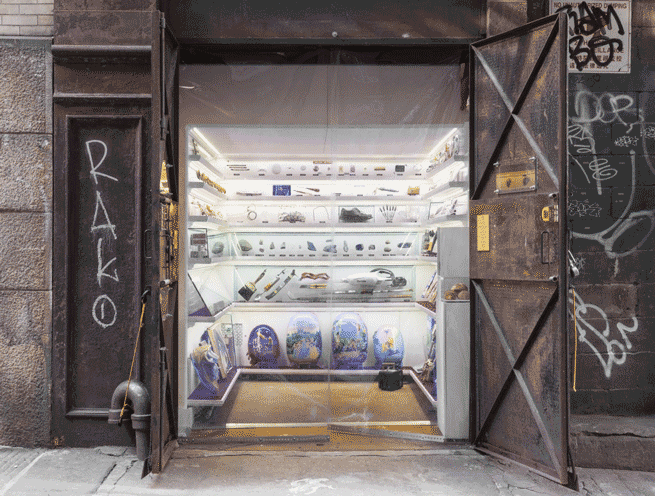

Collecting is an innate human tendency. It’s habitual when folx search for new material possessions, acquire trinkets, hold onto familial belongings, and long for nostalgic ephemera. And while collecting is an inherently human trait, the majority of individuals do not classify themselves as collectors. For most people, an image of an everyday collector depicts someone who ardently seeks, accumulates, and catalogs gatherings of particular objects whether they be vintage fashions, floral teacups, or Pokémon cards. An everyday collector sees value in keeping, protecting, and archiving the objecthood of things when others might not. They do their best to ensure that the value of their desired objects remains known and high.

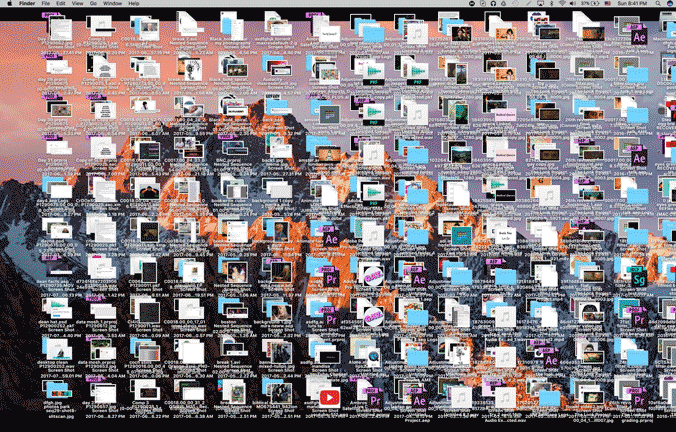

Through technology, humans collect digital data and digital objects every day, and people who participate in contemporary technology use––owners of computers, smartphones, and hard drives––are natural everyday collectors. Desktops hold piles of downloaded documents; iPhones store countless MP3 files; and social media feeds catalogue thousands of digital images. This sort of mundane collecting goes unrealized for a handful of reasons. For one, it is often a passive act as individuals hoard digital objects without recognizing it. Digital data does not take up tangible space, and digital clutter is generally quickly accumulated. Secondly, collecting digital data is precarious––a file can be as easily deleted as it is downloaded (it vanishes as quickly as it appears). Thirdly, digital data is not often considered rare and therefore is seldom considered valuable if it stays in its digital state. This low valuation occurs because files can be copied, duplicated, transformed, and transmitted endlessly. Duplicating a JPEG is a simple (and obsolete) feat in comparison to copying and recreating a physical one-of-a-kind Royal Doulton cup and saucer. Furthermore, a physical ink-jet print of a digital photograph is exponentially more valuable than the JPEG file from which the printed image derived from.

The storing of digital data is an incredibly important method of archival preservation for numerous individuals and institutions. Contemporary art institutions, for example, utilize digital archives which serve as secondary catalogs and counterparts to that of physical objects and archives. Digital archives frequently include images of artworks rather than the artworks themselves and may also contain copies of artwork authentications, research documents, and documents with pertinent information surrounding the history of an artwork. These secondary digital archives often act as information systems, and are frequently used by institutions to keep track of physical artworks, provide the public access to art catalogs, and to develop curatorial programming. Although digital archives are vital trackers for galleries and museums, they do not replace the objecthood and merit of physical and authentic art collections.

Lack of digital rarity and scarcity is the reason for why digital art, up until the last few years, has been predominantly considered a low form of art-making and undesirable to major contemporary art collectors. Art historian Perla Innocenti states that, “Digital objects - including digital artworks - are fragile and susceptible to technological change,” and therefore, “there are theoretical, methodological and practical problems associated with documentation, preservation, access, function, context and meaning of digital art…” Other forms of physically material art such as painting, sculpture, and photography, which can be easily identified as original, limited edition, collectible, and preservable have long been considered high forms of art, making them marketable in the contemporary global art industry. As Innocenti argued in 2012, “We no longer debate whether it is appropriate for museums to collect contemporary art. But despite the visibility and the status of media and digital art, many interactive and more complex digital works are still underrepresented even in leading museum collections.” For decades institutions have been hesitant in championing “A strictly techno-centric approach to media preservation…because digital art is not static or tied to a physical medium in the same way that analog art is.”

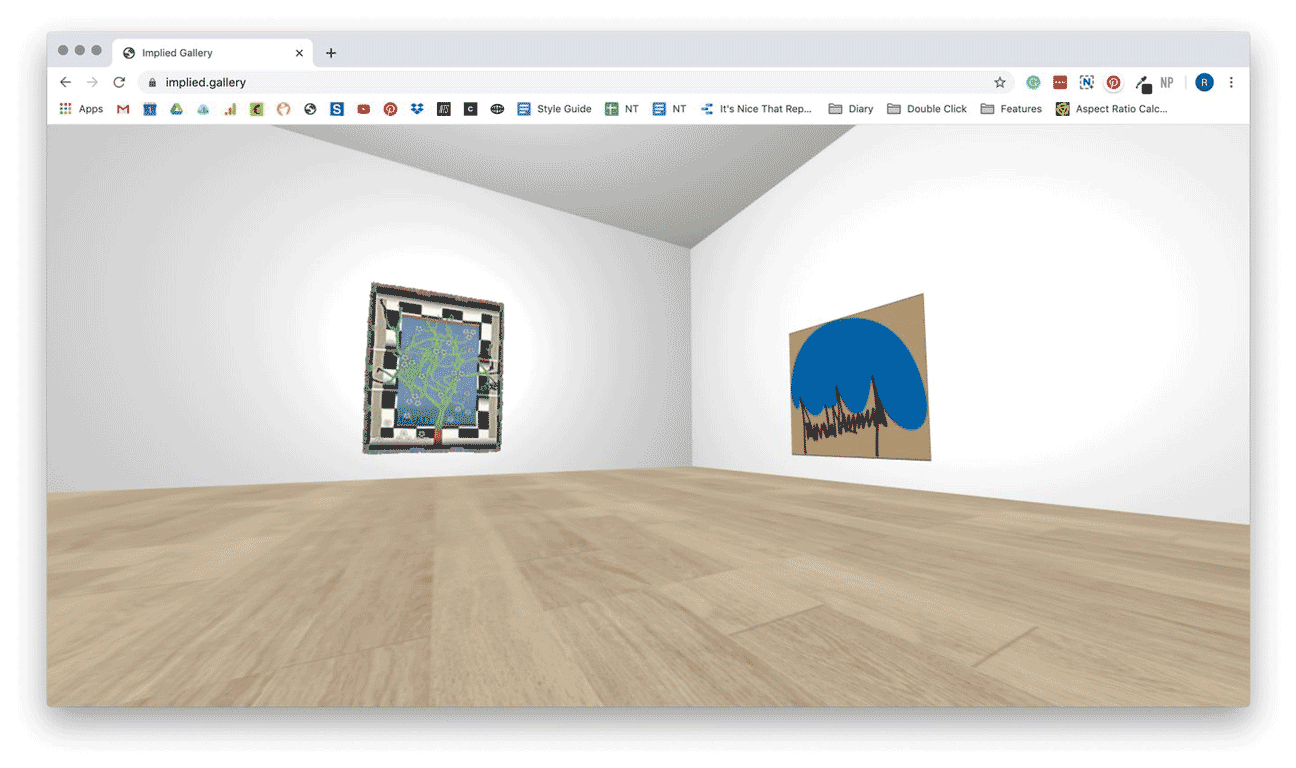

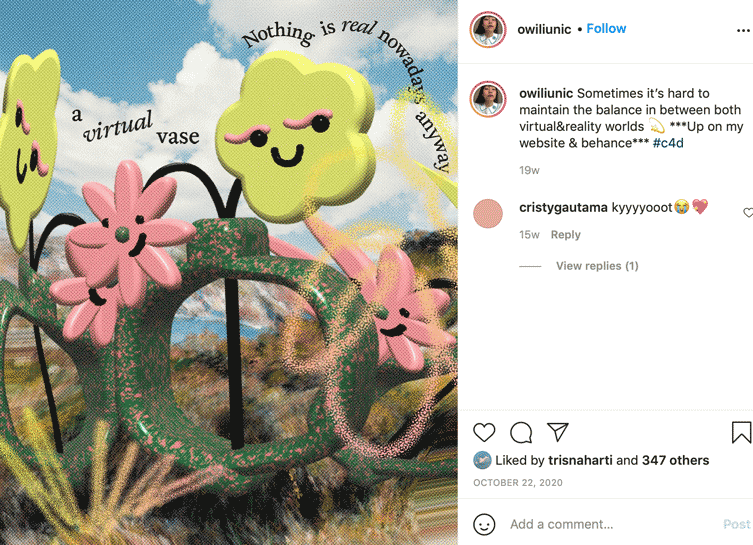

The medium of digital art has become increasingly popular over the past several years despite these challenges. New technology advancements as well as developed platforms for viewing digital art have unfolded through social media spaces, online exhibition websites, and virtual reality arenas. These virtual spaces provide the opportunity for digital artists to circulate their art through strictly digital means. This increase in the exposure of digital art hasn’t necessarily propped digital mediums into marketable realms of the contemporary art industry because while these platforms have increased the viewership of digital art, they haven’t solved the practical issues that accompany the collecting, preserving, and authenticating of digital art. Despite the reality that digital art medium is not new, the field of digital art has only recently become regarded as a collectible and profitable art medium. Many attribute this shift to developments associated with cryptocurrencies and crypto technologies.

Digital Art and the World of Crypto Culture

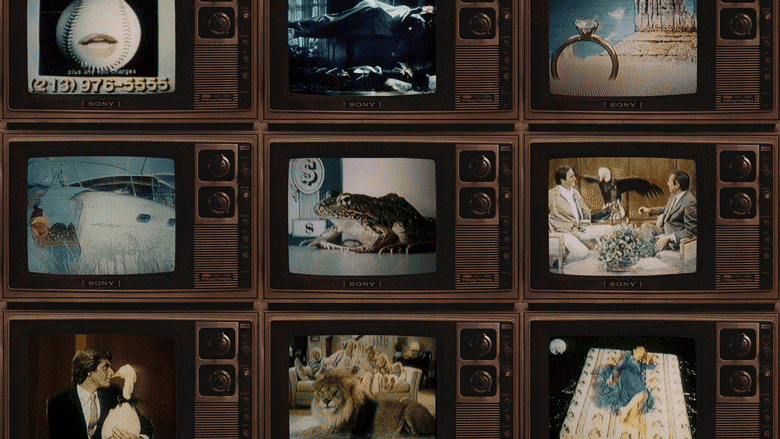

In the perspective of the Tate, digital artists are those who create art through digital means; digital art is frequently “computer generated, scanned or drawn using a tablet and a mouse.” Marie Chatel describes digital art as “technological arts, with fluid boundaries offering many possible interpretations of the terminology. She states that, “The term itself has evolved through time and whereas computer art, multimedia art, and cyber-art were standard in the 1960s-90s, the rise of the World Wide Web added a layer of connectivity resulting in a shift in language.” Different forms of digital art include, but are not limited to, mediums such as digital painting, digital photography, digital sculpture, animation, and Bitmap images (GIFS). As Katherine Thomson-Jones and Shelby Moser argue, “In its broadest extant sense, ‘digital art’ refers to art that relies on computer-based digital encoding, or on the electronic storage and processing of information in different formats—text, numbers, images, sounds—in a common binary code.” Digital artworks are often creative pieces that exist solely in the digital realm to be viewed through some sort of computer interface or screen.

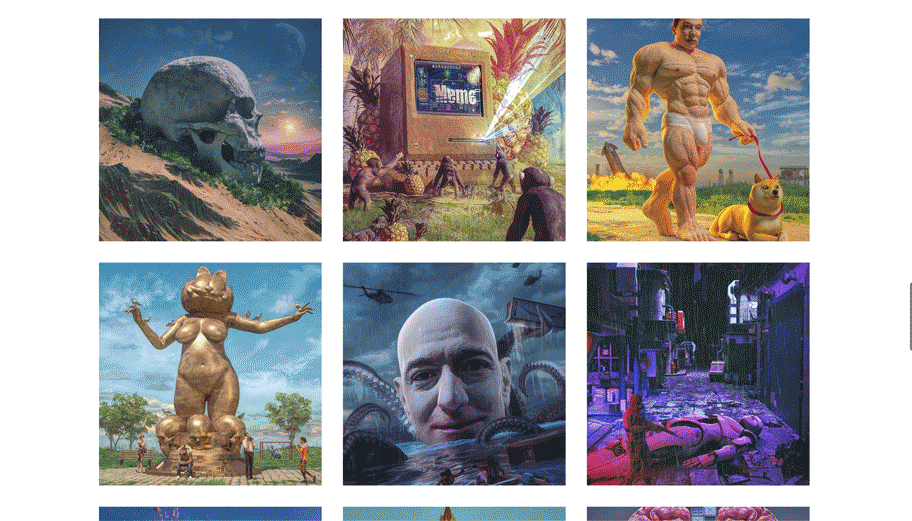

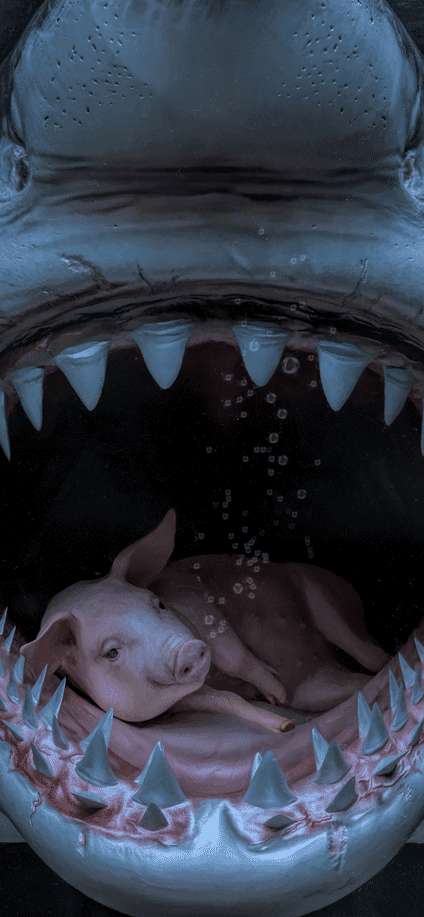

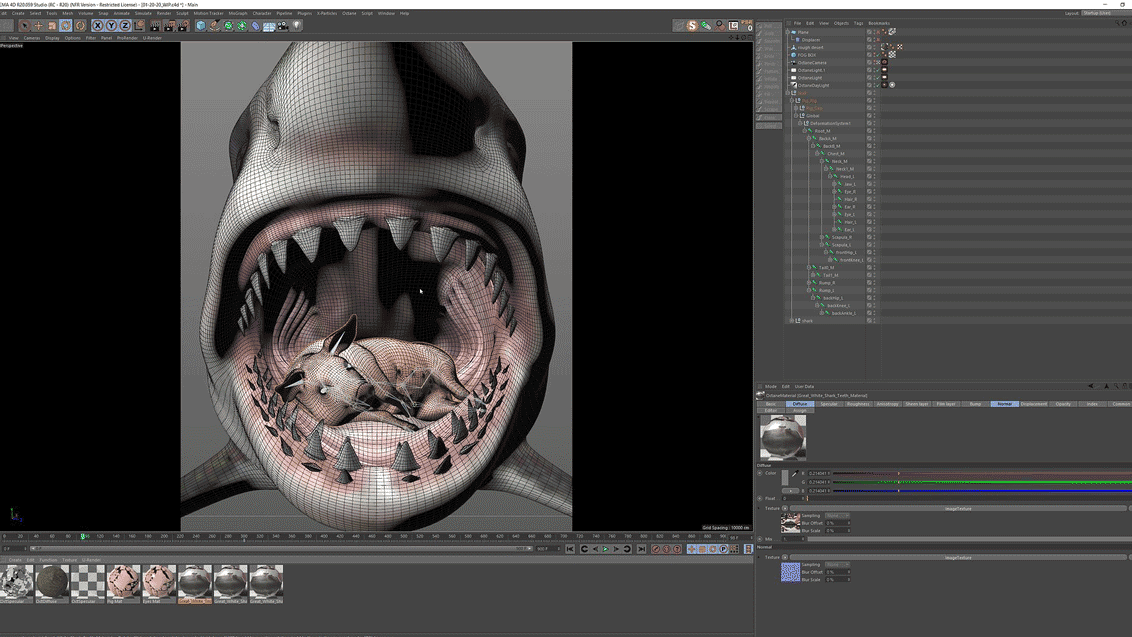

For 13 years, from May 1, 2007 to January 7, 2021 the digital artist Beeple (Née Mike Winkelmann) created one digital artwork per day. His greater series known as “everydays” includes individual artworks, which Beeple made through “ad hoc and unfiltered” processes, “with some pieces taking many hours and others dashed off in a matter of minutes…” Known for their provocative nature, his illustrative, digital pictures often capture an essence of the current time by responding to relevant societal and global events.

In creating a singular artwork every day for several years, perhaps as a modern day comparison to that of conceptualist artist On Kawara’s Today series, Winkelmann developed, “a framework for himself to freely experiment with creative tools ranging from 3D software to photography.” As Jesse Damiani argues, Winkelmann has “built up a library of assets that he can then reappropriate into new work—lending a level of quality that belies the fact that these pieces may have only taken an hour to generate. This is also how he’s able to publish 3D artwork that engages directly with political moments and memes in real time.” His ironic and wittily dark pictures can be downloaded for free via his website as digital wallpaper attachments. Alternatively, unique and authentic variations (that cannot be freely downloaded) are available for purchase via the blockchain platform and digital art market space, OpenSea.

On February 25, 2021 Christie’s, one of the world’s leading auction houses, opened bidding on a modified series of Beeple’s work titled Everydays: The First 5000 Days (2021)–– acclaimed to be “a monumental digital college,” and “a unique work in the history of digital art.” This moment introduced the world’s first ever major auction for a “wholly digital blockchain artwork.” Bidding for the work closed on March 11, 2021 and after the first seven days of the auction, the initial suggested bid of $100 USD has transformed into a stupefying bid of over $3 Million USD. By the time of its sale, the piece sold for a whopping $69.3 million, making it one of the most expensive auction works by a digital audience. Christie’s states that by, “Marking two industry firsts, Christie’s will be the first major auction house to offer a purely digital work with a unique NFT (Non-fungible token) — effectively a guarantee of its authenticity — and to accept cryptocurrency, in this case Ether, in addition to standard forms of payment for the singular lot.” For those who are unfamiliar with the intricate worlds, vocabularies, and interfaces that pertain to crypto technologies, the information surrounding this auction process, sale, and condition of Everydays: The 5000 Days may be difficult to grasp. Simply understood, this sale demonstrates that through crypto inspired technologies digital art can be made authentic, purchasable, and highly valuable.

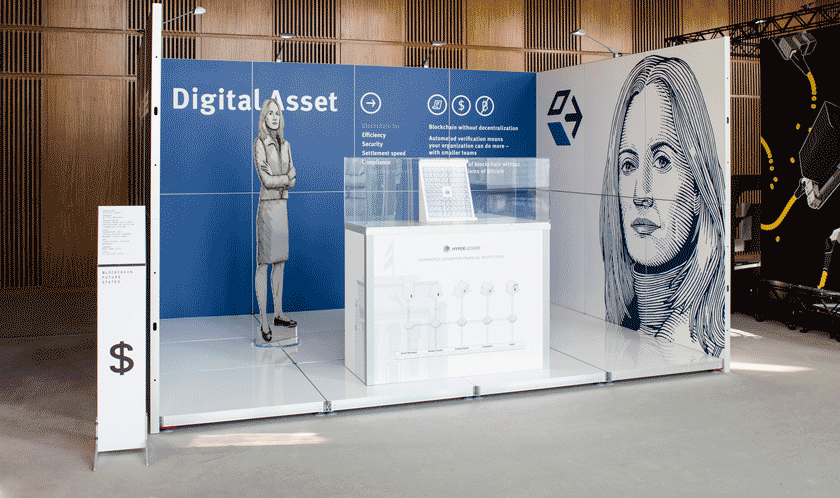

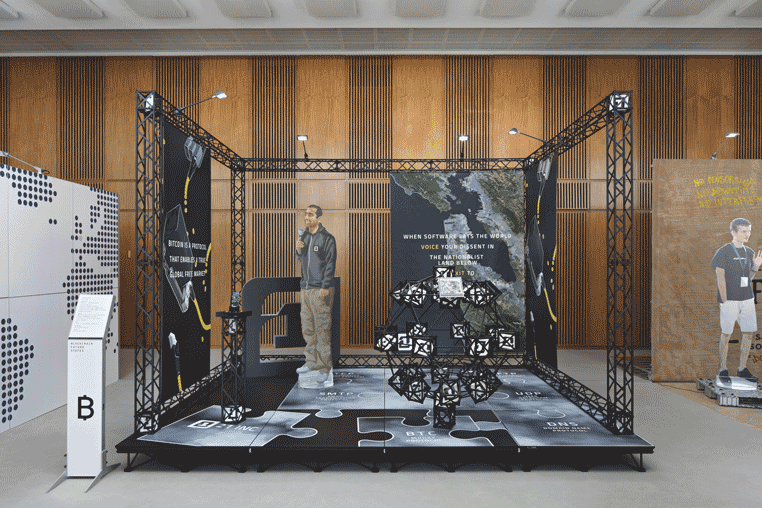

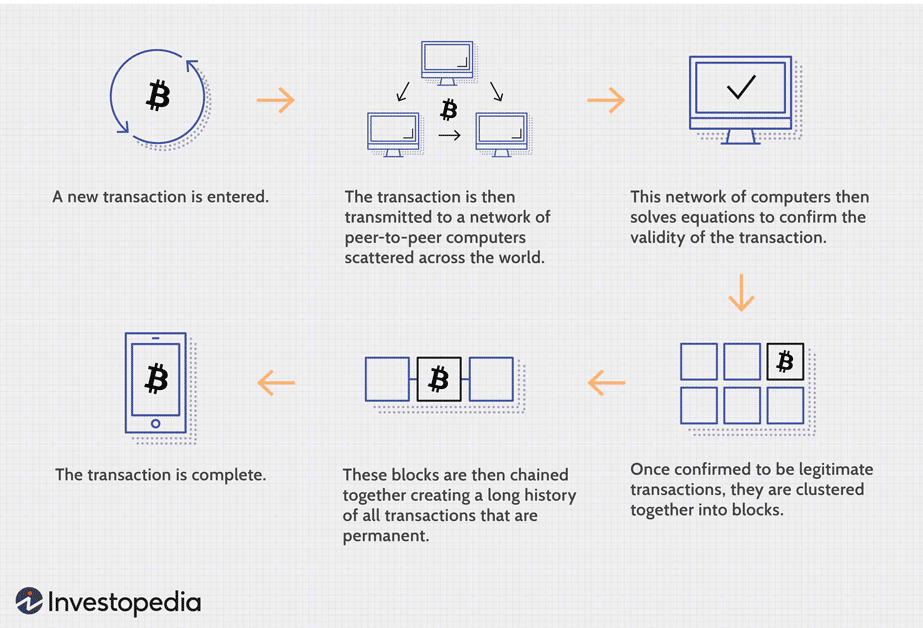

Crypto technologies are complicated in nature, yet everyday engagement with crypto culture continues to rise, and the use of these blockchain platforms as well as purchasing of cryptocurrencies has become a common practice for many individuals worldwide as a means of coordinating investments and substantiating finances. In a 2018 Ted Talk viewable on YouTube, the artist Gordon Berger proclaims blockchain to be “a revolutionary technology,” that “can make something that is digital equally or more valuable than something that is physical.” Berger furthers his discussion by asking the crowd: who is familiar with blockchain technology? Limited audience members raise their hands in agreement. He continues: who is aware of what bitcoin is? The majority of audience members raise their hands with familiarity. Berger states that “blockchain is the technology behind bitcoin, but it is far bigger than just that. You can imagine bitcoin as just one simple application that uses the blockchain to send money around, the same way that Gmail is one application that uses the internet to send emails around. Blockchain technologies can be used in many different spheres and industries, not just cryptocurrencies.”

According to Luke Conway, “a blockchain is a type of database,” whose purpose is “to allow digital information to be recorded and distributed, but not edited.” Hyperallergic journalist Rea McNamara articulates, “blockchain is a form of financial technology that acts as a permanent ledger distributed across multiple computers rather than just one. It’s basically a distributed database—a living, breathing spreadsheet operating in real-time—that audits itself.” Blockchains utilize built in protections within their networks and are “incorruptible.” They are extremely efficient at securing information.

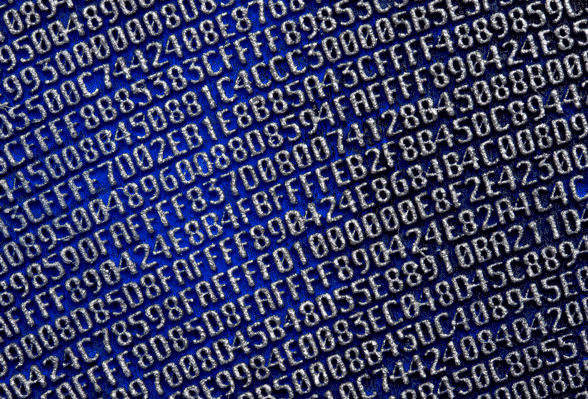

Online marketplaces such as OpenSea (which Beeple uses to sell various digital artworks), Nifty Gateway, and SuperRare are platforms that utilize blockchains to facilitate the sale of tokenized digital art. Julius Bär explains that “Tokenisation is the process of using a blockchain to issue a digital token: a unique string of numbers that can be used as a digital representation of a physical asset.” Bär elaborates, saying, “What’s unique about blockchain-based tokens is that they cannot be copied, forged or––once created––altered in any way.” Within the digital art market, when a digital artwork is purchased through cryptocurrency it is tokenized to become an entirely unique entity or, what is referred to as, a non-fungible token (or NFT). Non-fungible tokens cannot be swapped or exchange “like for like.” Instead, an NFT ensures that a digital artwork is sold and transferred to its buyer in the same way that a physical painting would go from the seller’s possession directly into the buyer’s possession and remain there until sold again. Through blockchain technology and tokenization, digital art can be made rare and, therefore, owned, collected, and re-sold. These advancements mean that digital data is no longer strictly considered precarious, copyable, and of little worth, rather digital objects are seen as quantifiable assets.

As Christie’s recent auction of Beeple’s artwork demonstrates, the exclusive contemporary art world–– the industry that makes up leading artists, galleries, and auction houses––is excited and ready to explore the potential effects that blockchain and NFT technologies have on the history of art. The everyday art world––regional artists, art consumers, art historians, cultural thinkers, and those who engage in visual culture––find these new technologies intriguing, but perhaps daunting. Some individuals are hesitant and critical of engaging in the cultural craze that crypto technologies have incited due to technological inconsistencies of crypto technologies and the mass ecological footprints that digital data mining creates. These criticisms should not be ignored; however, the issues raised do not alter the idea that blockchains and NFTs are promising for the future of digital art history for diverse reasons.

First and foremost, blockchain technologies are able to certify an artworks provenance, metaphorically and physically. In a 2018 panel at Art Basel Robert Norton expressed that blockchain technologies allow artists to time stamp data and certify that an artwork was made at a certain “moment in time.” When artists use this technology, it “ becomes a very valid form of evidence for the future and potentially helps protect them from fraudulent activity or unauthorized reproductions, and hopefully preserve value in the statement of those works.” With this, artists can easily authenticate digital artworks by proving their origin. These technologies allow artists to produce work in digital editions with a traced record of the editions’ origins as well. Furthermore, multimedia artists who create artworks that exist both physically and digitally, are able to authenticate the portions of their work that exist in the digital realm. Additionally, Bär maintains that “Blockchains are also enabling new ways of interacting directly with artists, creating direct markets between artists and collectors and paving the way for new forms of patronage.” In most parts of the world, visual artists are some of the only creative producers who do not receive resale royalties for their productions as once a work is sold, it is no longer the financial property of the artist. Jess Houlgrave, co-founder of Codex Protocol states that blockchain users can potentially “create alternative ownership models, “ for digital art, “whereby we either use smart contracts to enforce resale royalty payments or we can create fractional ownership models where an artist can retain an equity stake in their work and benefit from its ongoing performance.” Thus, artists and artist foundations can infinitely continue to profit and gain recognition from their work.

Interestingly, innovators, artists, and digital connoisseurs are excited about blockchain technologies because they believe that blockchain creates accessible platforms for direct artist and consumer interaction. Even though these technologies are now used to facilitate the sale of major artworks, blockchain technologies often operate on a micro level and offer peer-to-peer interactions. Houlgrave expresses that for her, “this space is all about diversity and it’s about diversity of people,” and artists of different backgrounds, geographies, political, philosophical, and educational perspectives. Gordon Berger states that “one of the main concerns of physical art is that it functions in this highly exclusive art market with many intermediaries.” Blockchain allows digital artists and consumers “to function in this totally open ecosystem regardless of your age, race, or education.”

In a highly digital world, crypto technologies are giving credence to the sort of everyday digital media that individuals might normally pass off as disposable and unworthy. For some, this shift in thinking is seen as optimistic and for others it is hair-raising. Through 2020 to 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic has shaped the way that humanity sees and engages with the digital world. With each new day, the digital realm metamorphosizes and society recognizes that the digital world is, in part, the real world. Virtual systems are affecting all facets of life and harbouring large effects on the history of digital creation. Undeniably, crypto culture is creating new means of human interaction with money, data, and even energy production, which in certain circumstances is concerning. The possibilities that crypto culture presents for artists and the history of artistic digitization seem invigorating, notable, and promising. As with any sector of the art world, positive strides are met with conflict, but sometimes conflict opens space for more contemplation, creation, and critique. Is crypto culture actively changing the livelihood of digital art objects? It will take time to realize the full effects of crypto art and to see how artists will truly engage with crypto technologies in the long term.