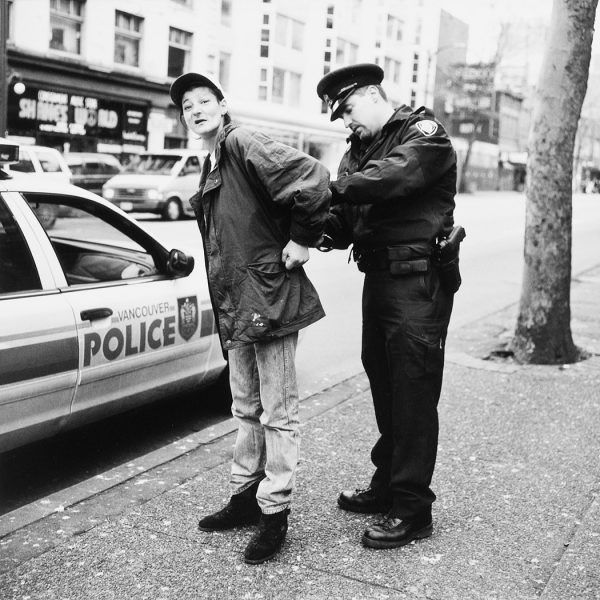

Stories about Vancouver's Downtown Eastside (DTES) are often told through the eyes of statistics, data and descriptions that portray its residents as victims and criminals living in "Canada's poorest postal code." At the same time, not enough is said about how ongoing social inequalities are the cause of multiple public health crises in this neighbourhood, including the opioid crisis present today.

Armed with his film camera and an empathetic worldview, Canadian photographer Lincoln Clarkes unknowingly embarked on a five-year project to humanize these statistics with the first portrait in his Heroines series in 1997. He talks of his friend Leah, who died in 1999 of a heroin overdose, and how she introduced him to Vancouver's "addicted subculture."

“We frequently ran into each other for near a decade,” he explains. “She was usually engulfed in bizarre, surreal situations. But it all started the summer morning of meeting Patricia Johnson, who eventually went missing, and her two girlfriends. When photographing the trio, it became a Film Noir episode of drama. The portrait of them strung out on the steps of the Evergreen Hotel on Columbia St. brought me to my knees and made friends cry. I willingly slid into the new obsession of documenting at that point, in the vein of Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis, portraying social injustice and calling attention to the plight of addicted women.”

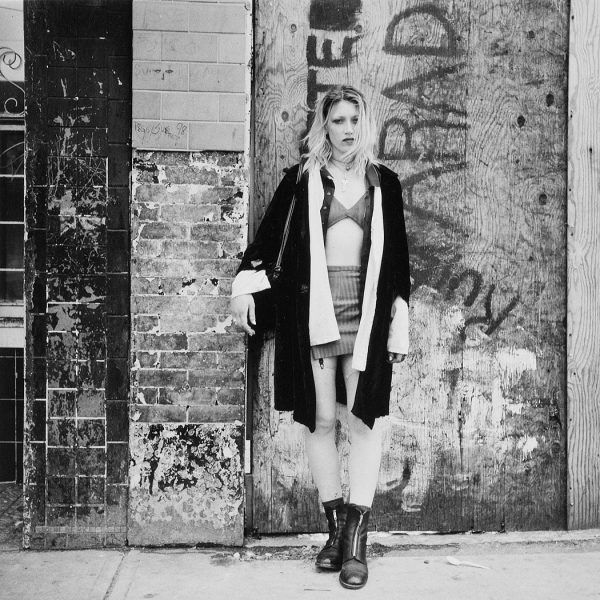

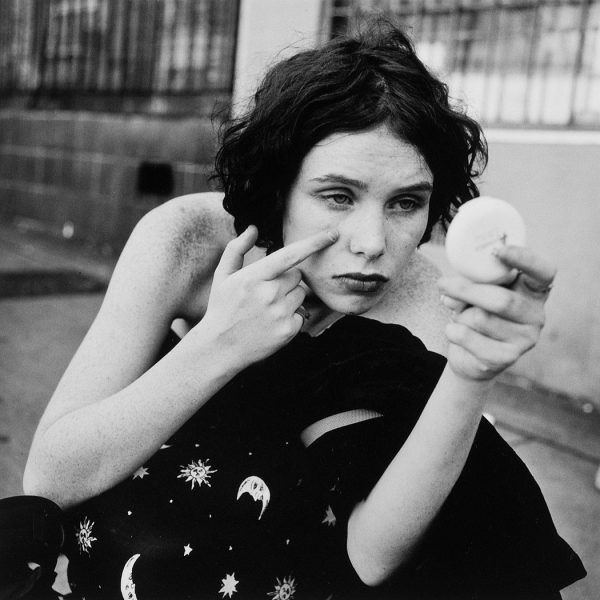

Clarkes began photography in the editorial fashion business. In an interview included in his book of photographs, Heroines: Revisited, published in 2021, he discusses the subjectivity of beauty and explains that this series is meant to subvert beauty and reveal it "as it is, raw, damaged, sick and sad, yet troubled and tender," shifting from photographing celebrities to beauty in its roughest form, with the only difference being that these women don't have the fancy accoutrements that accompany luxury.

A 2001 documentary titled Heroines explores Clarkes in his methods of photography and his relationship with his subjects, following six of these women.

Clarkes describes his work as “forcing people to look at these women, to look at the plight, to look into the eyes, to really see these women, not just as a junkie but as who they are: a woman, a child that’s grown up.”

I encountered this series at my local library in North Vancouver after stumbling upon Clarkes' book, Heroines: Revisited. I sat and flipped through each black and white portrait, feeling profoundly compelled by his work. Having grown up a majority of my life in Vancouver, I have interacted with this community fairly often. I've had a handful of conversations with people on the street and often pass familiar faces. Each time, I have invariably felt a strong sense of “sonder”—that these strangers passing by have lives as vivid and intricate as my own, and that they are continually being punished for existing in a space they have been pushed into by their experiences and social inequalities.

This is what the documentary showcases; it shows people, with the same complex and vivid experience of life as all of us, revealing that this is a much more complicated problem than most can imagine. The documentary begins by following Meagan, a woman living in the DTES. She shares her traumas—the death of her son, sexual traumas and personal stories—and explains that “getting off drugs” doesn’t stop any of these problems for her, and that her addiction merely covers these things. Once someone stops, they are faced with tensions between them and society. “Society doesn't change when you stop doing drugs,” she explains.

We also meet Wendy, a mother who struggles with the strain between motherhood and addiction, and Bernadette, who also shares painful life experiences that have led her to this place in time. She logically explains that, after enduring so much horror without readily available resources, “It helps to make you forget, because you're having to grind for it the whole time, so if you're thinking about dope, you don't have to think about anything else.” This is a recurring theme in the documentary. Clarkes' work, both in the photo series and documentary, shows how, without the right tools and resources, these women are condemned to this path and are in dire need of the right support to live healthy lives, presenting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for Good Health and Well-Being and No Poverty.

In an interview, Clarkes discusses how everybody is “suspicious in the heroin/crack ghetto, but it’s also a friendly place. When walking into those streets and alleys you're really walking into their living room, dining room, and bedroom.” To share a personal anecdote from only last month: I was outside of a concert venue in the DTES, having just lost my wallet with my ID, and credit/debit cards, trying to retrace my steps to where I could’ve possibly lost it. As the people around who lived on the street were seeing me look around, they were curious to what I was looking for.

A few people suggested that perhaps I had accidentally thrown it in the garbage and started showing me what they called their “tricks” to open the garbage bins and started helping me look. After a while, I sat with a man on the side and was laughing at myself for having lost it and missing the show I was there to attend. After talking for a little while, he started rummaging through his jacket, pulling out a $5 bill, telling me that it's all he has but maybe it’ll help me get home. These interactions are everywhere when you don't look away from these people.

“Heroine is the big scapegoat for the neighbourhood,” Clarkes says “The ‘big evil’ (...) what they need more than anything else is love, some real unconditional love. If they had that, heroin wouldn’t be in such hot pursuit.” Clarke speaks about not being ashamed of who these women are, how each photo is like they are coming up for air, looking at the camera in the eye and confronting the viewer saying, “It's me, here I am.”

See the Heroines documentary here and more of Lincoln Clakes' work, including the full Heroines photo series, here.