With such an opulent history woven into its delicate fabric, it’s no wonder pashminas have maintained their luxury status today.

Pashmina is a variant of the prominent cashmere (anglicized for Kashmir) fabric and is known for its handmade softness, warmth and design. The word is just as exotic as the fabric—pashmina comes from the Persian pashm or “wool”, but it actually refers to the handicraft by Kashmiri artisans in India. Pashmina should not be confused with shahtoosh, a different high-calibre fabric that has been banned.

This fabric is sometimes used to refer to the goats from where the fibre is collected. This fibre was first discovered and named by Mir Syed Ali Hamdan, an Iranian scholar who came across a breed of goats indigenous to the cold and high-altitude areas of the Changthang Plateau in the Ladakh deserts of Kashmir.

Producing pashmina fabric is done manually from start to finish—nothing is machine-spun or factory-made, which adds to its calibre and ensures a livelihood for all craftsmen involved in the process. The people who herd Changthangi goats are the nomadic Changpa herders from tribes inhabiting Ladakh regions bordering Tibet, China and Kashmir in India. Changpa herders rear livestock, horses and yak to produce, consume, and sell meat, but herding Changthangi goats is their main livelihood.

Changthangi goats grow an extra layer of wool in their undercoat to protect them from harsh conditions in the winter, and shed them in the spring—a process known as moulting. These fibres produce cashmere, but what’s special about pashmina is that goats aren’t shorn for pashmina’s softness. Instead, the fibres are procured by combing excess fine hair from the undercoat of the goats. This fibre has been termed finest in the world.

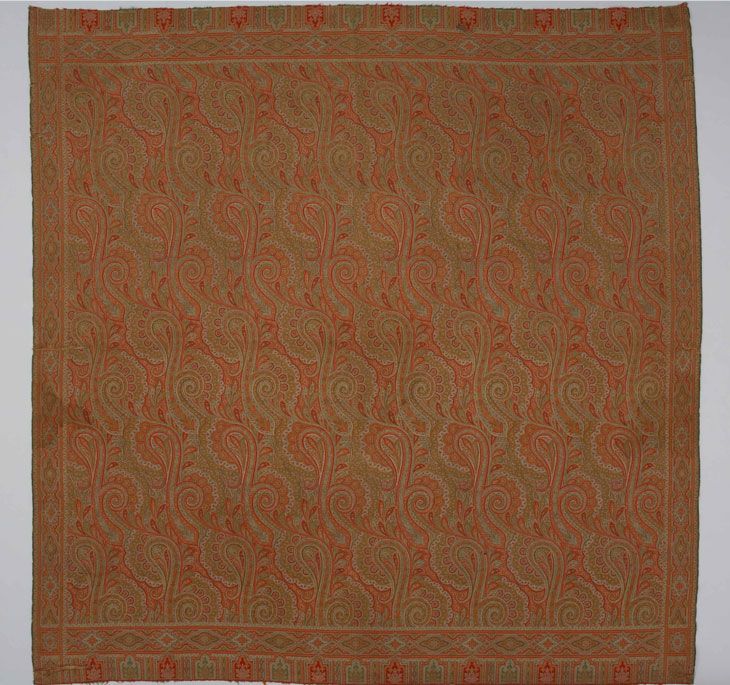

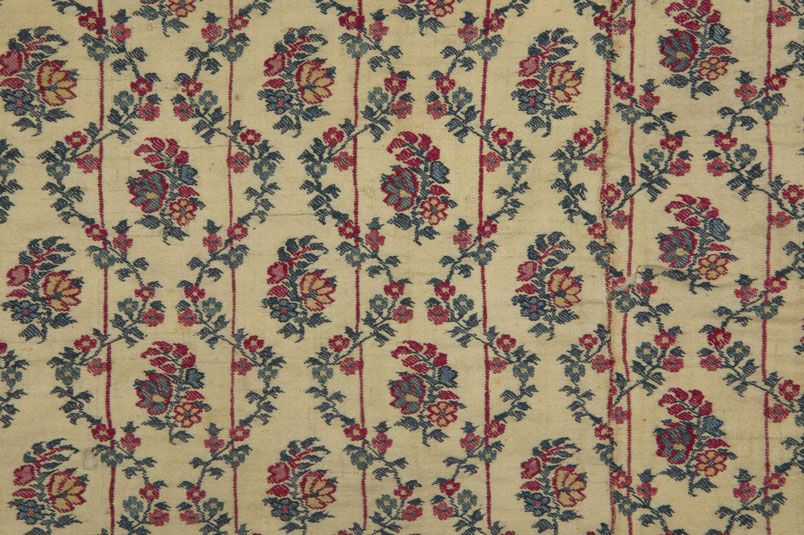

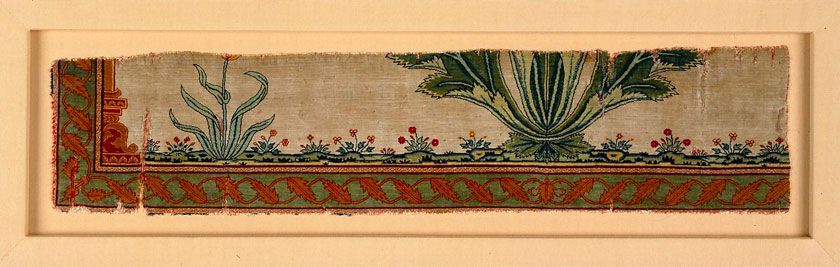

Changpa herders collect fine hair, but Ladakh doesn’t have its own textile infrastructure so the herders cannot complete processing the wool. In trading it with other heirlooms and artisans and strengthening existing infrastructures in parts of Kashmir, this step echoes the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for Decent Work and Economic Growth. Once the hair reaches Kashmiri artisans, it’s woven into fabric for furniture, scarves, shawls, wraps, prayer mats, carpets and accessories, and it is designed accordingly. Non-toxic dyes are used to preserve the fine fibres. The designs vary from embroidery to floral and paisley designs of leaves and mangoes, to interwoven vines, vases and more.

In the entire process of producing pashmina fabrics, no machines are involved—thus creating a livelihood for Kashmiri artisans and Changpa herders who raise the cashmere-producing goats. Pashmina’s status as a symbol of wealth has lasted for as long as it was discovered, particularly in India and Europe. In early 16th century India, Babur, the founding emperor of the Mughal dynasty in India, encouraged the use of pashmina to indicate rank, nobility, high service or power. He would use pashmina for shawls or robes and gift them to royal advisors and members of his darbaar (noblemen in his royal court).

This tradition was carried forward by his grandson Akbar, who conquered the Kashmiri territory in the mid-16th century. Akbar used pashmina shawls and robes for the khil’at, honorary ceremonies as part of the Mughal tradition.

Just as pashmina was popular for ceremonial use during the Mughal rule, it also thrived in India’s colonial era. Pashmina fabrics and industries flourished in 19th century India and England particularly among women. It was considered a feminine status of wealth since the English law at the time didn’t permit women to inherit property, and was used for coming-of-age ceremonies and weddings for girls to inherit.

They became well sought-after for being crafted from raw materials, their eye-catching designs, warmth and fineness of the fabric. Even the Empress Josephine of France was known to have worn pashmina dresses and shawls. Overall, pashmina seemed to suit European women since its floral designs and bright colours livened up dresses and provided warmth to countries with harsh weather conditions.

Pashminas have had an extensive history and timeless appreciation for their meticulous handiwork, but they’re more than just an expensive fabric. The process of producing pashminas is a livelihood in itself for herders and artisans in parts of Kashmir, India, and mirrors the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure.

World-renowned textile and art museums have put pashmina textiles on display, but the art itself is preserved when the artists are seen and protected. Today, pashmina styles are not endangered but their creators might be, due to having the region turned into a warzone and being prone to climate change.

However, digital sites like pashmina.com promote the use of pashmina fabrics and methods to uphold Kashmir’s cultural heritage and to “cater to the need of improving the future of our planet” using sustainable yet fashionable fabrics. This site’s commitment to preserving Kashmir’s heritage through producing pashmina styles reflect the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for Sustainable Cities and Communities, Responsible Consumption and Production, and Good Health and Well-being.