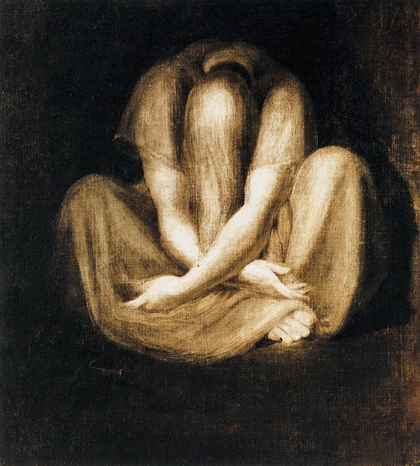

Horror art is most widely used as an outlet for catharsis: a symbolic place where one can go to release feelings of anxiety, experience adrenaline, or empathetically identify with the subject’s pain and suffering. The pinnacle of indelible horror, however, is achieved when the images illustrate something uncanny and more perplexing than images of pure physical pain and suffering – and in turn, reveals unexplored truths of the human psyche. The attraction to horror as an unpleasant experience situates itself in the basic desire to explore the psyche or the Self. The Self is a historically evolving concept in psychology. Still, it is rooted in the notion that both the conscious and unconscious work in harmony and that the various parts of one’s personality must be integrated to feel a sense of wholeness. Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) was among the first to address the need to acquaint oneself with the unconscious motivations of the psyche: “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.” For Jung, symbolism in art was one of the primary ways to express the darker truths about the human condition.

Jung’s work establishes such concepts as symbolism and archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the shadow remains culturally relevant and widely employed in mainstream dialogue when critically interpreting art. He believed that there is a universal lexicon of images and stories that indicate a fundamental similarity among people, specifically concerning how we relate to ourselves and others. Though the experience of humanity changes as society progresses, there are ideas, traumas, and desires that linger through generations. Art can serve as a guide for understanding collective perceptions, values, and in the case of horror media, its fears. The following is a close reading of two of the most famous paintings in Western horror art and a critical interpretation of the collective impression they make through symbolic language.

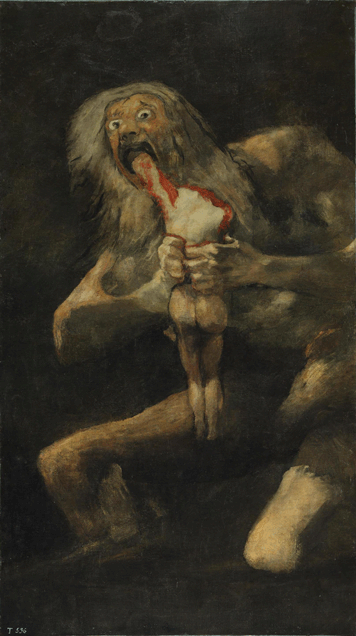

Francisco de Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son

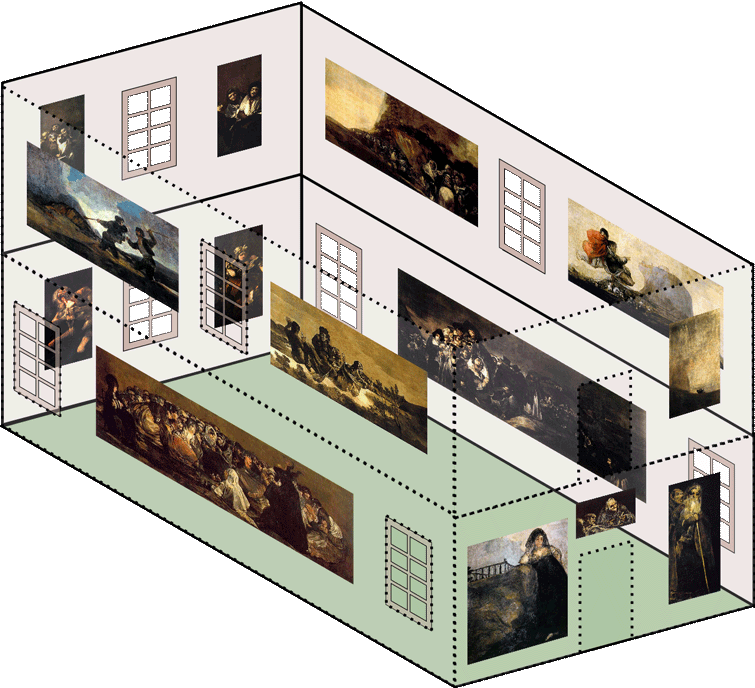

Francisco de Goya was in his early seventies when he painted a series of works now known as the Black Paintings (1819 – 1823), consisting of fourteen murals throughout La Quinta del Sordo’s two-storey villa outside Madrid, Spain. These murals were posthumously extracted from the house in 1874 and transferred to canvas for public display; the most notorious of these paintings, Saturn Devouring His Son, is currently housed at the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

What We Do in the Shadows

The murals were completed with a certain amount of privacy. Although their existence was not a secret, the work was made independent of commission or publicity and is considered to have been created solely for the artist’s benefit. There are no known notes by Goya on these works. Even the titles remained a mystery and were most likely never given by the artist himself; the names of the paintings as we know them were assigned by art conservationists, curators, and historians around 1878 when the murals were exhibited for the first time at the Exposition Univeralle in Paris, France (Licht 168). The painting, now known as Saturn Devouring His Son, initially situated in the dining room of Goya’s villa – an ironic placement considering the subject matter – is regarded as one of the most indelibly horrifying images in Western art, and one that is shrouded in ambiguity.

While the impetus for Goya’s creation of the Black Paintings remains unclear, it is generally thought that they were a cathartic exercise, created free from the implications of knowing the work would be critiqued and scrutinized. Goya painted these images of the psyche with freedom and abandon, resulting in work every bit as cryptic and existential as the mind itself. Critic Jay Scott Morgan speculates that Goya may have painted this image towards the end of his life as an untethered and therapeutic admission of the complex relationship with his son, Javier. The latter referred to Goya’s creation of the Black Paintings as being made in accordance with the freedom of his genius. As bleak as the paintings may be, the reward must have been the liberation of obstructed thoughts and feelings long left unattended, now manifested in these monolithic images. Created in privacy and with uncensored impulse, Goya conceived of an image that embodies secrecy and perversion, in which Saturn becomes the allegory of hidden urges and secrecy itself.

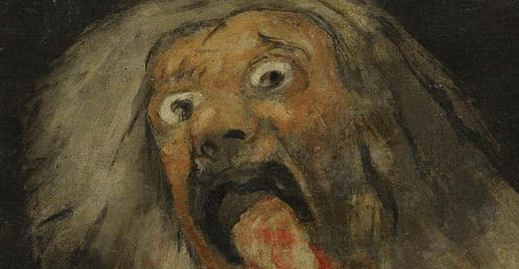

Goya’s Saturn, a frail and desperate looking man, situated in a cavernous black abyss, uses his teeth to tear the flesh from a small body clutched in his gnarled hands. He crouches awkwardly; his body vaguely deformed. Some critics argue that Saturn here is an allegory of the time or war, while the figure being eaten represents humankind. Goya had previously created a series of eighty-two prints now known as The Disasters of War (1810 – 1820, published 1863), as well as the painting Third of May 1808 (1814) depicting brutal images of murder and disparity about the war between the Spanish government and Napoleon’s army. Like the Black Paintings series, The Disasters of War series was not named by Goya himself, as they were not disseminated at the time of their creation - most likely due to the concern for his safety should the government retaliate against his criticism. While Goya has a prolific history of portraying images of war in his art, the narrative of these images is usually literal; many of The Disasters of War prints illustrate civilians being brutalized, murdered, and tortured by soldiers easily identified by their uniforms. The painting The Third of May 1808 commemorates a specific event referenced in the title, and wherein Spanish civilians were slaughtered under Napoleon’s occupation. There is little room here for ambiguity in interpretation. The narrative of Saturn Devouring His Son, however, is opaque.

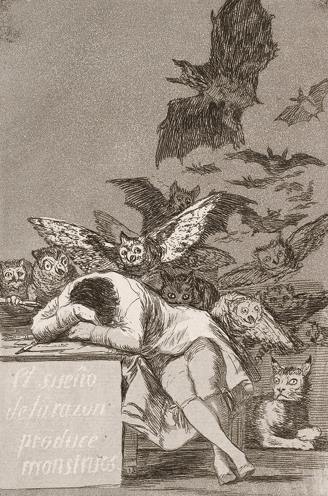

Goya’s Saturn draws on the motif of the psychological unconscious, an exploration indicative of a type of existential dialogue present in some of Goya’s previous work. His etching, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1797-1799) from the Caprichos (1797 – 1798) series depicts a man slouched over a table, his arms cradling his head while bats and birds of prey descend upon him. The man’s face is not visible; he is in an introspective state while these beasts flock towards his head and metaphorically into his mind. It is commonly analyzed that the Caprichos was meant to criticize the state of society. There is, however, a more individualistic interpretation of Romanticism to this work, a sense in which the state of the psychic self is being examined. The full epigraph on this plate reads, “Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united reason, fantasy is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels.” The monster, in this case, is sublime, inciting fear through its signifiers of predation, but welcomed for its ability to inspire creative insight. In its allusion to the terrifying unknown being the site of enlightenment, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters is a visual precursor to the ideas of Carl Jung and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900) regarding psychological and philosophical exploration into the darker realms of humanity. Nietzsche proposed, in his book Beyond Good and Evil (1886) that when you chase monsters, you risk becoming a monster yourself, and“when you look into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.” This proposal, like Jung’s concept of the shadow as a necessary aspect of a complete psychological framework, demands that we look into the metaphorical darkness to see the greater scope of our psyche. In the context of Saturn Devouring His Son, the act of seeing is the true content of the work, turning a grisly act of cannibalism into an allegorical dilemma of seeing what we do not wish to see and knowing what we do not want to know.

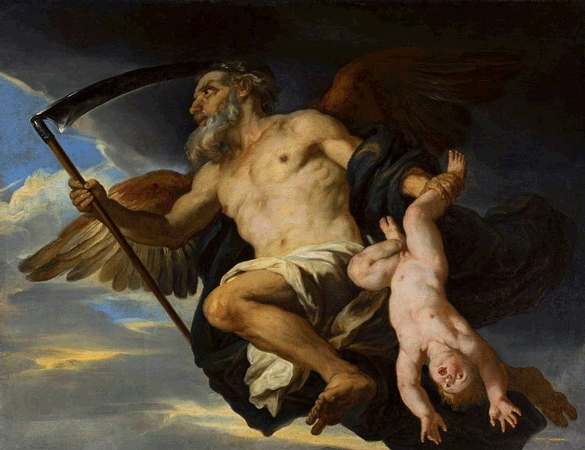

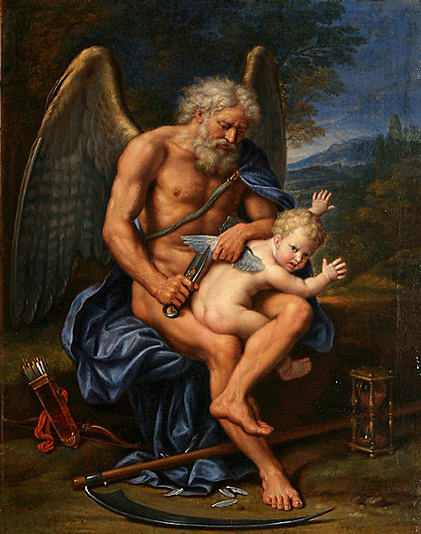

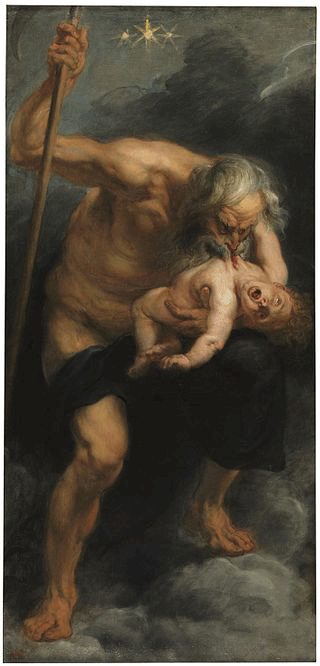

Given that the work was titled posthumously, and because the painting lacks the typical iconography of the Kronos myth, the figure in Goya’s work is not necessarily Saturn. In classic Greek mythology, Saturn devours his son to prevent the child from usurping his authority and power; Saturn consumes the Other for fear that the Other will become independent of him, and in doing so, have the potential to destroy him. The Greek Titan, Kronos, also known as Saturn in Roman mythology, is often thought of as an allegory of time. It is usually depicted holding a scythe, the tool to cut down crops during harvest season: a marker of the passage of time. In one of the Kronos narratives, the Titan is so fearful of the passage of time, the inevitability of growing old and being usurped from power by his sons, that he cannibalizes them to prolong this fate. The Saturn - or Kronos - the narrative is easily identifiable in art by three signifiers: the presence of a scythe, Saturn as a physically powerful and robust man, and the abuse of an infant. Italian painter Giovanni Francesco Romanelli’s (1610 - 1662) Chronos and His Child (Early 17th Century) depict a virile winged man ascending towards the sky, scythe in one hand and a terrified infant’s ankle in the other. French painter Pierre Mignard’s (1612 - 1695) Time Clipping Cupid’s Wings (1694) illustrates a more relaxed Saturn as he calmly and symbolically devastates the angry-looking child on his lap by clipping the child’s wings with a pair of shears; the scythe is still present at Saturn’s feet.

The decidedly brutal depiction of Saturn and the one that most closely resembles Goya’s work, and which bears the same title: Peter Paul Rubens’ (1577-1640) Saturn Devouring His Son (1636) portrays a man standing in an abstract landscape, hunched over the screaming child he holds in one arm as he uses his teeth to rip the flesh from the child’s chest. The painting is horrifying in the hauntingly vivid portrayal of pain in the child’s face, twisted in reaction to the atrocity inflicted on him. From Romanelli to Rubens to Goya, the victim child is taken, bitten, and half-eaten, respectively. The most notable difference, however, between Goya’s Saturn and the others is the interaction between Saturn and the viewer.

Now You See Me

The true subject of Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son is the gaze. The painting’s notoriety and the stunningly direct and immediate impression left on the viewer are contingent on one simple aspect of the painting: Saturn’s eyes. Saturn stares directly through the canvas toward the viewer, and appears in the middle of the atrocious act, leaving no room for denial. Just as Goya never intended for an audience to see this painting, Saturn did not intend for Goya to bear witness, as he, Saturn, rips through flesh in this primal scene of cannibalism. The gaze in this case represents something much more unsettling than merely being witness to a crime; because of the interaction between the subject and the viewer, or rather the subject’s awareness of the presence of the viewer, the gaze posits accountability of any witness. As the subject is caught committing a crime, the gaze creates a dialogue between Saturn and the viewer, as Morgan describes, “I seem to be a participant as well as viewer, I look upon him, and I am implicated in the crime.”

The act of voyeurism on the part of the viewer raises questions of responsibility. In seeing the criminal, the viewer is not only confronting him, but being confronted in return by his gaze. He is aware that you have witnessed his crime, making you implicit in whatever happens next, and making Saturn’s gaze an effective tool in mirroring the dark nature of Jungian Self. We are unwilling participants in this crime, not merely voyeurs. This transaction invites one to look inward at their own dark impulses, and the nature of their own secrecy. By unintentionally engaging with his audience, Saturn’s secret act of consuming the Other is exposed, and therefore made real and undeniable to the viewer having witnessed it. This act of destroying and consuming another for the nourishment of oneself is the manifestation of Saturn’s impulses. Without the reflection of his action made possible by the gaze of the viewer, however, Saturn may continue in this pathological act indefinitely. Our arresting gaze represents the pivotal discovery of Saturn’s crime, and now that his darkest nature is witnessed, it can never be unseen.

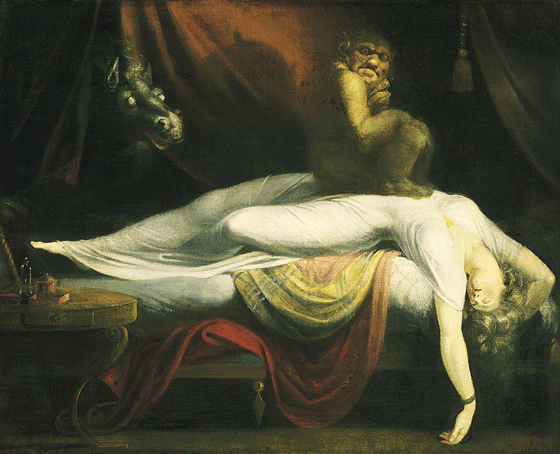

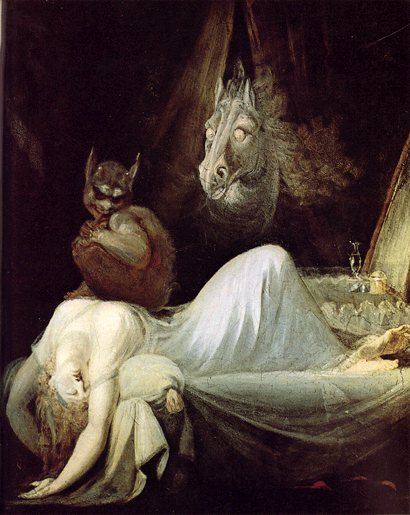

Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare

The socio-political upheaval during the time The Nightmare was created, paired with the literary influence of the painting, make this image a benchmark of cultural discourse. Sigmund Freud (1836-1949), contemporary of Carl Jung and founder of psychoanalytic dream interpretation, was a noted fan of Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), and was said to have kept a print of Fuseli’s The Nightmare in his Vienna study. In an avant-garde testament to Freud’s later work, Fuseli himself once proclaimed: “[Some] of the most unexplored regions of art are dreams.”

The content of The Nightmare was nothing new. Myth and folklore have a long-standing focus on symbolic narratives of dreams, sleep, and fear. In ancient Greek mythology, the god Pan (half man, half goat) would leap from out of the woods, frightening travelers and inducing dreams or visions often accompanied by terror and anxiety; this is the origin of the word panic, hence the term panic attack. In Norse mythology the Mara was a spirit that suffocated sleepers. The German words for nightmare, alptraum, meaning elf dream, and alpdruck, meaning elf pressure, indicated a malevolent creature intruding on the sleeper, causing physical and emotional suffering. Aside from the somatic experiences of fear, nightmares have in turn been recognized as a source of revelation. The French word reve, for dream, and the English reveal, both stem from the Latin revelare, meaning to uncover or lay bare, and in Dutch folklore the nightmare caused victims to leave their bed in the act of somnambulism (sleepwalking) and sometimes experience clairvoyance.

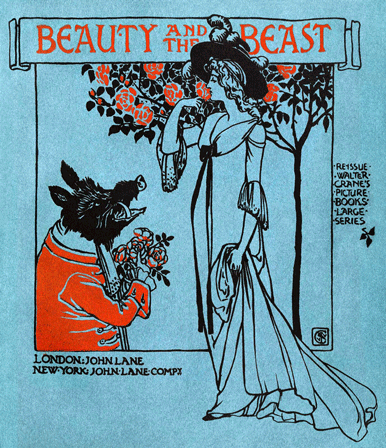

Fairy tales, while similar to myth, are adjusted over time to reflect the socio-political climate from which they are altered. Commonalities are evident in theme, archetype, and plot, but with clearly distinguishable changes in narrative and literary aesthetic as the story evolves within the cultural dynamic. With each retelling of the story, a new layer of meaning is added in deference to the cultural climate and socio-political issues. Classic elements such as unconsciousness, strange love, fear, anxiety, and revelation are central to The Nightmare, but under new circumstances.

Beauty and the Beast

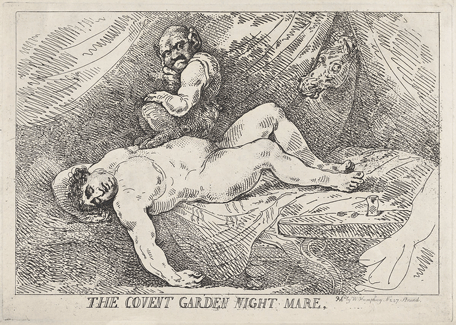

As represented in The Nightmare: A woman lies histrionically, sprawled on her back, her arms slack over her head, while a monstrous creature sits contemplatively on her chest, his chin on his fist, his eyes cast towards the viewer. To the left, a wall-eyed horse peeks his head out from between the dark curtain in this carnivalesque tableau. The beastly male and the beautiful female became a popular literary trope in the 18th century Western world. Bestiality, the animal bridegroom, and the sinister male lover are prominent themes in Aarn-Thompson folklore classification dating back to the early 1600s. It was not until widespread publication, however, that fairy tales including Jeanne- Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s Beauty and the Beast, published in England in 1756, became staples of popular culture. These stories are meant to symbolize redemption, or the taming of the beast. In presenting the trope as a nightmare instead of a love story, Fuseli touches on a more sinister interpretation of human nature.

As the title suggests, The Nightmare represents unpleasant visions during sleep, a concept that would later be described by psychologists as the unconscious manifesting itself in dreams. The painting’s horse at first glance presents a somewhat comical addition to the painting, as art historian Andrei Pop describes, “literally a night mare, as both contemporaries and scholars have pointed out with some embarrassment at the obviousness of the pun.” The horse was most likely a rebus, a puzzle constructed of pictures signifying a word or phrase. To observe the horse was to know you were dreaming, as Pop concludes, “the sense of sudden realization might be what Fuseli meant to convey of the nightmare experience.” The absurdity of the horse’s expression, its dumbfounded gaze and eyes that beam with glowing light, are symbolic of the shock of the unconscious becoming conscious. Furthermore, the scene witnessed by the horse as well as the viewer indicates a disturbance of sexual mores; sexual disruption is often thought to be the driving factor of nightmares. Anthropologist Charles Stewart notes: “since the advent of psychoanalysis, the concept of ‘repression’ has often been applied to account for the erotic nightmare.” The figures in The Nightmare, from the left to right progression of horse, to humanoid, to woman could also be seen as the varying attitude towards sexuality, in a time of tension between extreme societal sexual repression and a libertine uprising. The horse is the voyeur, it stands gawking with eyes that shed light on the scene it beholds, perhaps envious of the liminal figure, the man-beast at the center who straddles the line between human and animal. This creature stares back, not at the horse, but at the viewer. He is unsympathetic to the horse’s dismay because he has elevated himself to the highest and most participatory figure in the scene, fully aware that he is being watched.

The creature symbolizes the duality of the civilized person who wavers between human and beast. Finally, the woman: her robust figure, silken gown, and the refined furniture surrounding her all indicate her wealth and status. Her eyes are closed to the situation around her, or perhaps she is simply lost in ecstasy. Both reactions – disgust and intrigue – may also be interpreted in equal if not simultaneous measure. A contemporary of Fuseli, the infamous Marquis de Sade commented on the subject of Western sexual repression, “lust’s passion will be served; it demands, it militates, it tyrannizes.” For all the perplexity of the erotic nightmare symbolism as fear of the sexual Self, there is a less ambiguous fear represented here: fear of the ungodly Self.

The Beast in Me

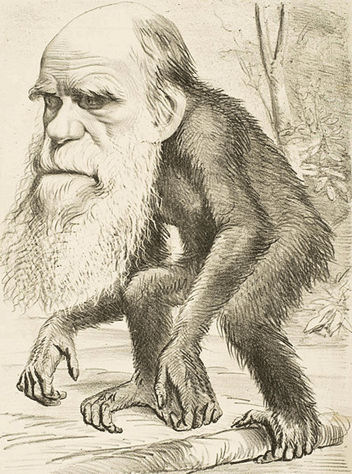

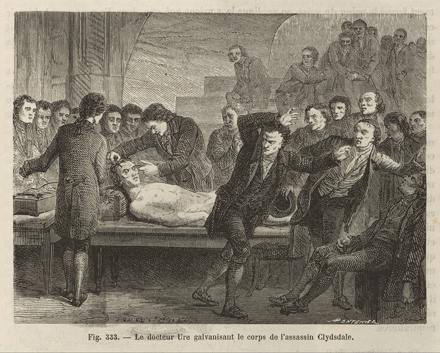

The Enlightenment, a philosophical movement of the 18th century that emphasized reason over tradition, and the separation of church and state, marked a pivotal time of unrest and a cognitive dissonance for those who considered humans to be divine by right. Thomas Malthus published the first of six essays in 1798 declaring Earth not fit to sustain growing populations in light of industrialization. The core of Malthus’ argument was that people needed to regulate population growth as natural resources were not designated to us in infinite supply. This offered subtext to what Evolutionists would later state: we are not living fatalistically and that nature, not God, would determine our lives as a species. Charles Darwin publicly presented the idea of natural selection in 1838, and subsequently published On the Origin of the Species in 1859 together with fellow biologist Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace is known to have independently hypothesized natural selection and published his own papers on the matter in 1858.

The collective fear of evolution was the fear that humans were not made in the image of God, but descendent from single-celled organisms followed eventually by simians. The humanoid or the uncanny figure was most certainly newly allegorical of nightmares. According to Freud, the uncanny causes irrational fear and discomfort by seeming strikingly similar to something, but not being the authentic thing itself. This would be the collective nightmare: a world in which humankind was not created in a godly image, but instead had evolved gradually over the course of millions of years. In response to growing terror of the primitive animal instincts within the Self, the uncanny in horror literature began its rise, and in some cases, the literature can be directly linked to Fuseli’s painting.

Early evolutionist and occasional poet Erasmus Darwin (father of Charles) was so inspired by The Nightmare, that he expanded his poem on evolution, The Loves of the Plants in 1789 to include two descriptive stanzas of the image:

On her fair bosom sits the Demon-Ape

Erect, and balances his bloated shape;

Rolls in their marble orbs his Gorgon-eyes,

And drinks with leathern ears her tender cries.

Edgar Allan Poe references a Fuseli work in The Fall of the House of Usher in 1839, and proceeds to describe irrational fear through a metaphorical incubus sitting upon his heart. Poe would later write The Murders in the Rue Morgue in 1841 in which an orangutan accidentally slits a woman’s throat while trying to imitate the actions of a man. In its outrage, the uncontrollable beast then strangles the woman’s daughter. However, the ultimate literary work encapsulating the fear of evolution was Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, published in 1818. The idea of human-as-beast and the fascination with monstrousness were growing in both the art and the scientific worlds. Percy Bysshe Shelley, husband of Mary Shelley, was known to conduct amateur scientific experiments in his room while attending Oxford University; he was also becoming increasingly radical in his anti-religious ideology, as influenced by Mary’s father, William Godwin. Deeply entrenched in the tensions between God and science, Mary would use her waking dream of a mad scientist creating an abomination of God and turn it into the classic novel, Frankenstein.

The monsters of both Frankenstein and The Nightmare demonize the uncanny human and call into question the very essence of humanity. As The Nightmare’s beast sits upon the woman’s chest, looking brazenly at the viewer, there is a sense that although it has done something wrong, it cannot be held accountable. The creature is malformed, degenerate; its shadow on the back curtain resembles devil’s horns, emblematic of the absence of God and virtue. The creature is fearsome because it represents something not wholly unlike ourselves, the disdainfully familiar, and the worst aspects of humanity. In the evolutionary context, Fuseli’s The Nightmare represents a fear that remains to this day, that we are the monsters, culpable in our own right and not gifted to the world through divine inheritance, but as accidents of nature.

Horror art allows us to explore our corporeal fragility from a safe vantage point. We are inextricably drawn to the monstrous, the evil, and the dark aspects of life in art because from there we can quell our anxieties in virtual experience. When art embodies the individual’s and the collective’s deepest fears, impulses, and desires, it imprints on the mind of the viewer and endures throughout history by means of the truth that it speaks.