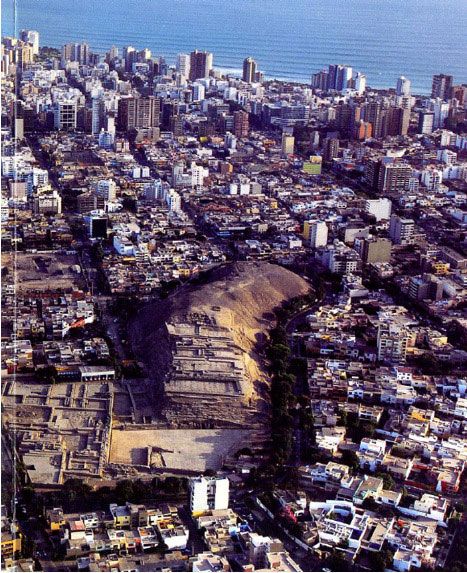

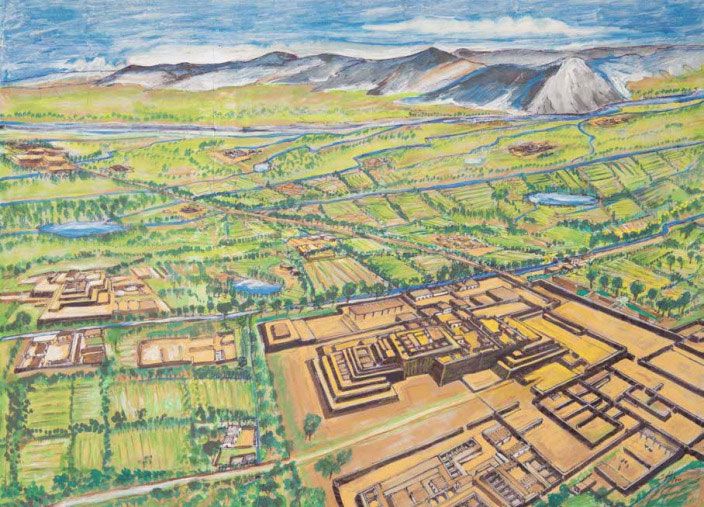

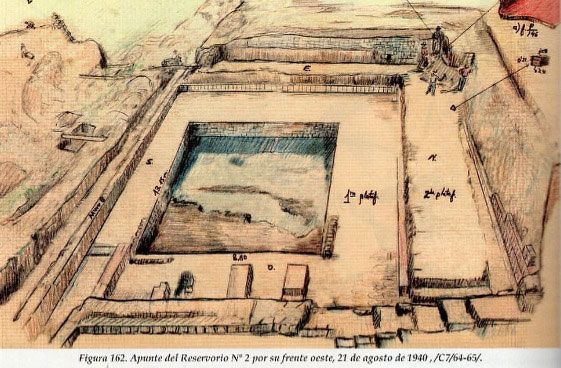

Waterecosystem is an artistic installation and winning project of the National MAC (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo) Art and Innovation Award 2019 in Lima, Peru, by the artist Ana Teresa Barboza and the architect Rafael Freyre. The installation takes inspiration from proper water management created by the First societies, such as the irrigation canal system and the wachaque. These technologies allowed the development of self-sustaining urban and agricultural spaces in desert territories and contributed to creating a singular, living and sacred landscape.

Therefore, the hydraulic work management transformed the coastal desert valley into a fruitful area, where the population saw water as an element of sustenance and a deity. At the same time, ceremonial temples were built.

The water cycle plays a fundamental role in Lima's ecosystems. In the coastal desert, the cold Humboldt current cools the coast and the warm upper layers of the atmosphere, creating a cloud cover that contributes to the use of water by the ecosystem of the coastal hills. They condense humidity, capture it, and take it to the ground. As for the primary sources of water for Peru's coast, there is surface water from rivers coming from the mountains, groundwater and coastal wetlands.

Coastal wetlands are the most productive ecosystem in the biosphere. Thanks to the totora and cattail, fibrous and phytodepurative plants, these wetlands serve different purposes, such as being a natural filter, controlling flooding, recharging aquifers, purifying water, stabilizing coasts, being a reserve of biodiversity, and mitigating climate change. The totora and cattail also have a cultural value as they serve as a tool to manufacture utensils, furniture and architectural elements.

For this reason, the artistic installation Waterecosystem allows the public to recognize the wetland ecosystem, now in danger of disappearing, in an immersive and interactive experience to enhance its cultural and ecological value in the territory and daily life. Likewise, this artwork brings up some of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals such as: Clean Water and Sanitation, Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure, Sustainable Cities and Communities, and Climate Action.

Firstly, Ana and Rafael had a look at the ancestral technique, the wachaque, which was vital to reproduce the cycle of water in an enclosed space, as it put on the table the technical way to make it possible. This was the spine of Waterecosystem.

On the other hand, the weavers played another essential role in making the installation possible. Here, we want to mention the Goicochea brothers (Samuel, Ever, David), craftsmen who specialized in weaving with natural fibers, using the totora and reed plants.

Waterecosystem, naturally, takes us very deeply into its functions to let us see how impressively the mist is when showing its power to give life to so many bodies, even when it seems to not exist as it is almost untouchable and unseen to our eye, "... with it comes matter, weavings, the totora, the cattail," says Rafael to G. Gargurevich.

Trees and plants capture the mist and have the role of transforming it into very tiny drops of water, to later fall to the ground and reach the wetlands by its subterranean fluxes and create multiple lives. Finally, the totora and cattail purify the water, which will be suitable to drink.

How does this installation work? How was it placed?

“The mist was created in a museum room by propelling water with a 50 bar pressure pump, a simulation of the water intensity when falling from a 20th building floor. In doing this, the water is sprayed and reduced to 50 microns to later pass through a cattail tissue with tillandsias. Afterwards, the water is transformed into 2-3 mm drops falling onto a volcanic stone by gravity, a filter that mineralizes the water and makes it drinkable thanks to the activated carbon and the quartz sand it contains,” as described in Revista J.

What would come to your mind if you were experiencing this installation?

Imagine yourself into this space; imagine how step by step you start to think about why your body moves and breathes; how, suddenly, you start to figure out your body moves because of the water you have inside and you drink every day. At the end, you just realize the profound dependence existing between the water cycle and you.

What do you think you would like to do afterward? Well, this experience will undoubtedly serve as a seed to flourish thousands of innovative ideas for preserving water as it easily conveys its role in the planet and our life.

Waterecosystem can be understandable for anyone without distinction (kids, adults, elderly), perhaps because the installation's message came from nature and it’s received, primarily by our bodies, as an unexplored canal of acquiring knowledge that could help us reorient our relationship with water.

As Rafael and Ana, there are other kinds of voices reaching this goal, as it is the case of the ONG Los sin agua, a community that created the Atrapanieblas, fog catcher in English, a mesh made of plastic material with small holes that, placed in an ideal way and in a strategic place, allows up to 400 liters of water per day to be produced per panel, through vapor condensation of atmospheric water. The water is later collected by a system of pipes and tanks for domestic and productive purposes.

This is an example of a solution based on nature to reach sustainable cities and communities. Implementing proper management and support to the water cycle, not just in a micro-scale but in a macro one (LEIS and Plan Met 2040), will secure a sustainable urban development and regeneration of the planet.

It is a call to rethink how we build cities, in whose expansive process, the relationship between the ecological infrastructure and the memory of the place plays a crucial role. Social, self-management, awareness and appropriation practices are essential in sustainable water management, as a resource, entity of life and heritage.