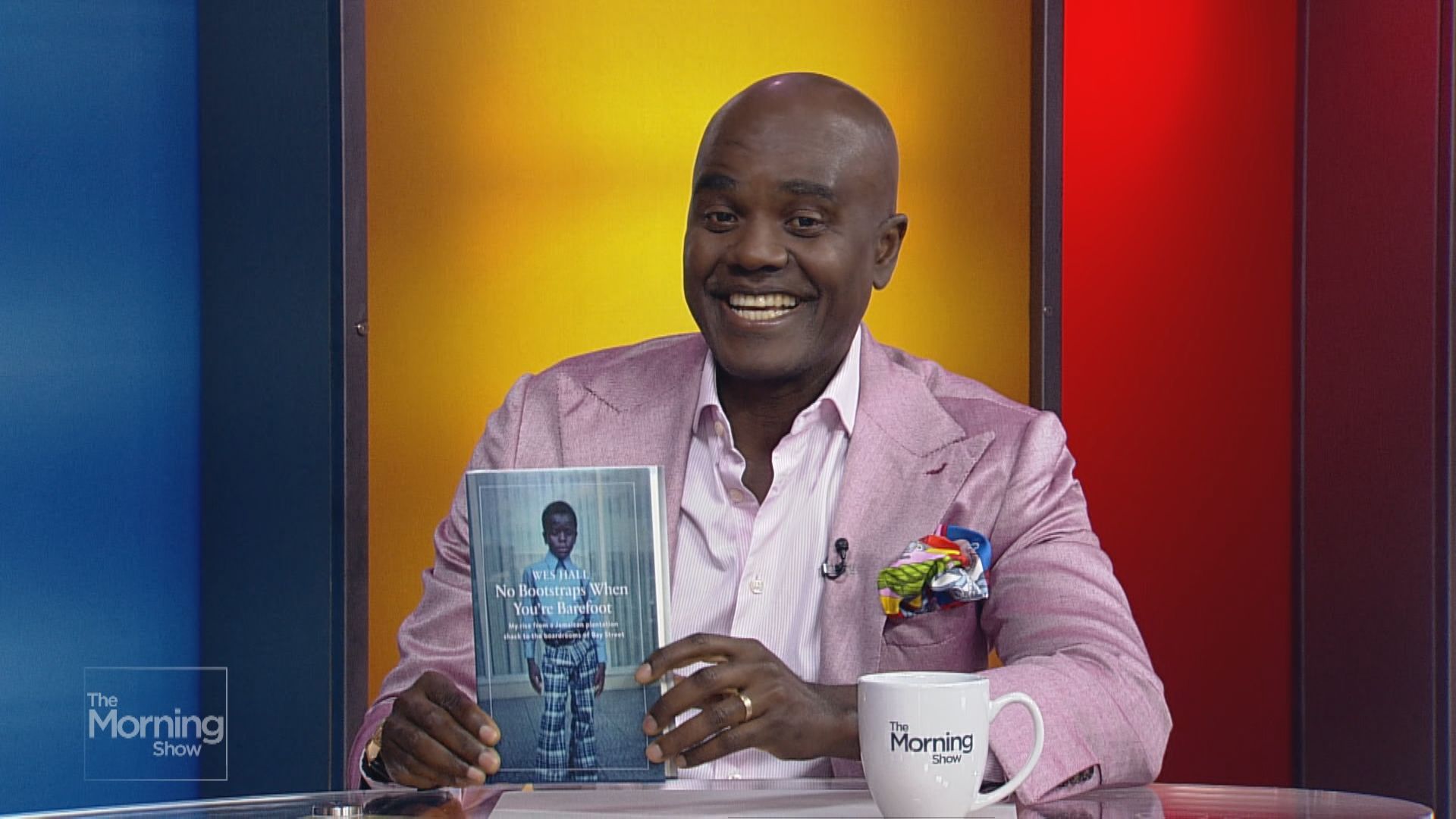

In his best-selling memoir, No Bootstraps When You’re Barefoot, Wes Hall shares his experiences with discrimination as a Black businessman in Toronto and sheds light on systemic racism through the lens of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for Reduced Inequalities.

Born on May 8, 1969, in Winchester, Saint Thomas, a small town in rural Jamaica, Hall's life started with humble beginnings. Abandoned in a tin shack by his mother, Hall and three of his siblings were taken into the care of his maternal grandmother, Julia, a farmhand on a nearby plantation.

However, unbeknownst to them, his grandmother had a full house of dependents, reliant only on her meagre worker’s wages to sustain them all. As a result, Hall and his family grew up in extreme poverty, living in a neighbourhood known as “The Barracks'' where opportunities were limited and indoor plumbing, electricity and running water were nonexistent.

Circumstances shifted when he was just 11-year-old. After years of infrequent visits and minimal contact, his mother showed up and demanded that he live with her at her home in May Pen, a bustling town halfway across the island.

In the two years that he spent with his mother, he was subjected to extreme physical and emotional abuse that threatened his self-esteem and ultimately, his life on a daily basis. On numerous occasions, he was degraded, humiliated and told that he wouldn’t be successful due to the colour of his skin.

Although this treatment was intended to destroy him, Hall was still able to navigate his life with a sense of self-confidence. He did well in school, built strong relationships and learned the importance of responsibility from other members of his community. Recognizing her inability to break him, his mother kicked him out at 13, leaving him once again to fend for himself.

For the three years that followed, Hall was forced to rely on his street smarts to survive, picking up odd jobs for extra money and depending on the hospitality of neighbours for a place to sleep. However, at 16, he was sponsored by his father and brought to live with him and his family in Canada.

There, he was exposed to a new environment, full of growth and opportunity. Little did he know, there were greater obstacles in place for some more than others.

In his teens, one of Hall's first jobs was as a security guard at an office building in Toronto. During his time there, he noted that his white supervisors would fabricate complaints against him – the only Black employee.

They would criticize the way he spoke and how he dressed and accuse him of not completing tasks as if deliberately trying to get him fired. However, without definitive proof of racial discrimination, he was unable to act.

“It would be next to impossible for me to prove otherwise, and that’s the point. One of the ways [systemic racism] protects itself is by building in this kind of deniability,” he wrote in the book.

Systemic racism is the institutional assumption of discriminatory policies and processes that benefit white people and disadvantage people of colour. This is seen most notably in the educational, justice, employment and political systems where they’ve been embedded for centuries.

From microaggressions to blatant acts of discrimination, racism is not an uncommon feature of the Black experience. As Hall notes in his memoir, “When you’re subjected to racist attitudes and expectations in your life, you develop a keen barometer for them…[You] know when it’s about race.”

According to the Boston Consulting Group, while half of Canadians claimed that discrimination against Black people is “no longer a problem,” 83 per cent of Black Canadians reported experiencing unfair treatment at least some of the time. In another study conducted by York University in 2021, 96 per cent of Black respondents said that racism is a problem in the workplace, with 70 per cent reporting experiencing racism regularly.

Hall alludes to this racism when discussing another encounter, wherein his colleague told him he’d never be able to become a law clerk at their company.

In the book, he accepts that his skin colour was the driving force behind the comment, but notes that, at the time, “[he] was blind to the systemic barriers thrown in his path because he was raised in a place that didn’t have them.”

While his Canadian-born siblings were familiar with this system of inequality, Hall had been raised in a country that was 92.1 per cent Black. In Jamaica, Black people were visible at all levels and positions in Jamaican institutions, whereas in Canadian society, there were "limitations and exclusions" that defined who was allowed to occupy certain spaces and who wasn’t.

As he rose to prominence in the corporate world, Wes often found himself being the only Black person in these spaces. This led to him being consistently underestimated by people who, he claims, likely viewed him as a “dumb Black guy who grew up in a shack and never went to Harvard.”

According to Policy Options, Black leaders hold less than one per cent of executive roles and board seats in major Canadian companies. This hindrance of career progression can be attributed to many factors, including low rates of sponsorship, discriminatory practices and systemic biases in hiring and promotion processes.

Throughout the book, Hall references other situations wherein his Blackness created additional obstacles and blockages in his career. But rather than allow that to dictate his future, he chose to see being Black as a "superpower" that allowed him to bring a different perspective and lived experience to the table.

With optimism, personability, and a strong drive to succeed, Wes was able to overcome these systemic barriers and become one of the most influential business leaders in Canada.

In 2020, he established the BlackNorth Initiative, an enterprise that supports businesses in addressing and eliminating systemic barriers.

Under this agreement, leaders pledge to address racial equality in their companies and strive to meet measurable targets, including increasing their Black student workforce and Black executive/board members, offering mentorship to Black-owned businesses, and funding Black-led organizations and initiatives.

Thus far, the BlackNorth Initiative has received the commitment of over 200 of Canada’s leading companies, including Scotiabank, TELUS Corporation, Air Canada, and KPMG.

As Hall articulates beautifully in the book, “Each of us needs to take meaningful action to dismantle the system we inherited and apply an unparalleled effort to build a better one.” By creating opportunities for change, we ensure that all people are able to move forward and create a bright, fulfilling future for themselves.